Reflections on ORFC 2025

Talking about food in Palestine, imperialism in trade, and much more

Isabela here, writing to you from the skies as I return from two days at the Oxford Real Farming Conference (ORFC) 2025. The ORFC brings the alternative food and farming movement together every January, attracting farmers, growers, activists, policymakers and researchers from around the world.1

We were honoured that Feminist Food Journal (FFJ) was invited to ORFC as a media partner this year, and I’m so glad that I was able to make it to the conference in person. In the past, I’ve left conferences focused on “sustainable” development feeling drained, and frankly slightly cynical — but I left ORFC feeling quite the opposite. It was inspiring to attend an event that so integrally wove questions of gender equity, racial justice, and neurodivergence into its program — both in terms of session content and the support available for attendees.

I was also impressed by the exceptionally diverse array of professional backgrounds represented in the crowd at ORFC. Not only did I appreciate the conference’s commitment to bringing in a massive contingent of farmers, but I loved meeting journalists, chefs, academics, entrepreneurs, and more. Outside of FFJ, I’m in the third year of a PhD focused on inclusive food systems transitions and I do consulting work related to food policy and advocacy, so I was super excited about having the chance to connect with many people that I have only or mostly met online — including my beloved consulting clients Feedback Global, the ORFC dream team, and brilliant (and fun) food systems researchers at TABLE.

It made me beam from ear to ear to see FFJ’s logo printed on the back a programme carried in nearly 2000 sets of arms — clutched against chests as people hurried down the high street or set down on table tops while they fuelled up at cafés.

The conference takes place in venues disbursed around Oxford, which has the triple benefit of 1) keeping things exciting, 2) allowing you to get your steps in, and 3) acquainting you with the city. Zoë did her Master’s degree here and I loved imagining her running around to exams in her black robes and hat (people who study at Oxford actually do this!). Despite the chill, a shock for me coming from Barcelona, I found the city quite charming. Next year I’ll take more time to explore.2

The rest of this newsletter is a recap of the seven ORFC sessions I attended, including photos, audio recordings, and links to further resources. There were so many exciting things happening simultaneously that it was hard to choose which to attend, so I’ve also hyperlinked to a few sessions I didn’t make it to. That way, if they also sound interesting to you, you can find out more about the topic and speakers (if there’s no hyperlink, look them up in the programme for more information). And because it feels like there was just so much to say, this email is best read in a browser with the footnotes!

A perk for premium subscribers…

This summary newsletter is available to everyone but if any premium subscribers are interested in my full notes from any panels, please get in touch with me at isabela@feministfoodjournal.com and I will share them (I’ll do my best to make sense of my unintelligible scrawl). I would also be happy to schedule a more general food systems chat on Zoom!

THURSDAY

MORNING

What I attended: Roots of Resistance: Farming in Palestine (Speakers: Lina Isma’il, George McAllister, Cathi Pawson / Chair: Muna Dajani)

This session was totally packed. I turned up right at the start time after filming a short interview with Jackie Turner from TABLE, and we couldn’t find seats! Jackie and I ended up watching the livestream first sitting on the ground in front of what we soon were told was a fire escape, and then, more respectably, from a quiet room for participants around the corner.

The panel centred around the stories of women farmers in the West Bank and Gaza, and looked at how for Palestinians, food is about more than just nutrients or availability — it is about connection to the land. The brutal conditions imposed by Israeli occupation and genocide have led to rising enthusiasm for agri-tech solutions that claim to improve efficiency (much like we see in the West in response to the climate crisis); however, these threaten to displace ancestral knowledge in Palestinian agriculture. The panellists discussed how, against this backdrop, there has been a resurgence in interest in food sovereignty among young Palestinians. While food is often missing conversations on what the “day after” the current genocide in Gaza looks like, whether the scales tip should tip towards “climate-smart” high-tech agriculture or agroecology is a critical part of them.

Further resources:

What I wished I could have also attended: Rituals for the Land (Speakers: Manchán Magan, Angharad Wynne, Hop, Eddie Rixon / Chair: Rachel Fleming)

What I attended: Growing the Rainbow: LGBTQ+ Perspectives in Landwork (Speakers: Ali Taherzadeh, Umulkhayr Mohamed, Anna Barrett, Ben Andrews, Shane Holland / Chair: Vera Zakharov)

This session offered queer perspectives on land movements and farming in the UK. Its panellists included representatives from land alliances, Slow Food, and the head of the LGBTQ+ farmers’ network Agrespect, who spoke about the importance of re-establishing links between queer people and the land. Much of the discussion focused on how to reframe the countryside as a vibrant, tolerant place so that queer people aren’t forced to choose between living their full lives in a city or hiding their identities as farmers. Homophobia in rural spaces must be challenged through political education and advocacy movements, and interwoven with our struggles for a more sustainable food system: as Farmer Ben put it, “Why should people ‘buy British’ if they think the food’s origins are homophobic?”

When an audience member asked about how more queer people can gain access to the land, one panellist noted that there’s much room to innovate: much like queer perspectives have done for concepts like the nuclear family, people can look at forming co-ops, collectives, or working out of urban areas. “It’s about bringing radical ways of thinking into farming,” said Umulkhayr Mohamed. They noted that queer experiences of marginalization can help us to appreciate the marginalization of more-than-human beings in our ecosystems, and bring this appreciation into how we grow food.

Further resources:

What I wished I could have also attended: Disobedient and Convivial Approaches to Transformation (Speakers: Michel Pimbert, Sagari R Ramdas, Alejandro Argumedo, Nina Isabella Moeller, Grazia BorriniFeyerabend, Dee Woods / Chair: Colin Anderson)

and Cultured Meat — Gamechanger? Disruption? Or Just Hot Air? (Speakers: Jonty Brunyee, Andrew Court, Pat Thomas / Chair: Lisa Morgans)

and Farmworker struggles in Britain: Voices from the Frontline (Speakers: Catherine McAndrew, Valeria Ragni, Júlia Quecaño / Chair: Tara Wright) — but thankfully FFJ reader Anoushka Zoob Carter was there to summarize it instead:

This session aimed to inform attendees about the abuse of seasonal migrant workers in the UK agriculture sector. Júlia, who is from Bolivia, bravely presented her — and many other workers’ — mistreatment as a farm worker on a UK fruit farm called Haygrove in Herefordshire. Julia’s testimony, and those of many others across farms in the UK, is an indictment of the UK’s Seasonal Worker Visa scheme. Alongside 88 Latin American seasonal fruit pickers, Julia staged the UK’s first-ever wild strike by workers on seasonal visas, over wage theft, discrimination, racial abuse, and harassment. Julia is mobilizing under the slogan “justice is not seasonal: from the farm to the table, we are all free and equal”, and she and her comrades will be taking to the streets on the 25th of January to mark the beginning of a campaign that will involve an Employment Tribunal claim.

AFTERNOON

What I attended: What does an anti-fascist farming movement look like? (Speakers: Alex Heffron, Tom Wakeford, Sagari R Ramdas / Chair: Sophia Doyle)

I have less cohesive takeaways from this session, as I ran into Jonathan Nunn from Vittles and was so excited to chat that I left my notebook in a bag across the room. But this panel did an excellent job of situating discussions around the food system in our wider, largely right-lurching political contexts. Panellists discussed recent calls for farmers to defend British farmland from immigration — including with this nauseating quote from UK TV commentator turned Conservative-farming icon Jeremy Clarkson — and the links between fascism and farming, including the birth of organicism and its origins in conceptions of racial and corporeal purity.

Sagari R Ramdas critiqued the world’s largest experiment with agroecology in Andhra Pradesh, India. Despite the veneer of progress it suggests, Ramdas says that at its core, the agroecology program is a mechanism of fascist Hindu state control to perpetuate caste inequalities, including (in)access to land. In her view, any “sustainable” solution that leaves Brahminical-patriarchal capitalism untouched is not a true solution — and food must be at the core of any anti-caste movement, given that unequal land access and dietary norms are both key ways that caste inequalities manifest.3

Somewhat tangentially to the panel but vital to the overarching theme, an audience member noted how the so-called “green transition” in the Global North itself often imposes great injustice on people in the Global South, highlighting the bloodshed, land-grabbing, and labour violations resulting from mining in Africa to make batteries in electric cars.

Further resources:

Ramdas, S. R., & Pimbert, M. P. (2024). A cog in the capitalist wheel: co-opting agroecology in South India. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 51(5), 1251–1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2024.2310739

FRIDAY

MORNING

What I attended: Smash Imperialism! For A New Trade Framework Based on Solidarity (Speakers: Anuka De Silva, Edu H. Nualart, Carson Kiburo, Sophia Doyle / Chair: Alex Heffron)

This session focused on how free-trade agreements perpetuate neocolonial forms of extraction, dispossession, and violence and recreate imperial relationships between the Global North and South — a “death-bringing colonialist system” with food at its core. I wanted to attend it as I recently wrote a comprehensive report on this topic for Feedback EU: ‘Trading Away the Future? How the EU’s agri-food policy is at odds with sustainability goals’, which looks at how trade in commodities like soy encourages the growth of a climate-wrecking livestock herd in Europe while enabling deforestation, land-grabbing, and the use of dangerous agri-chemicals in origin countries. These injustices have gendered impacts, given women’s unequal exposure to pesticides, specific reproductive health risks, traditional dependence on forest resources and more precarious access to land and capital.

Speakers on this panel included a woman farmer from Sri Lanka and a Maasai lawyer from Kenya, who shared how trade frameworks have impacted their communities by forcing unwanted products on them or disabling their traditionally pastoral ways of life. A representative from Slow Food spoke about reforming World Trade Organization ruling and frameworks to avoid perpetuating these harms.

Something I loved at ORFC2025 — perhaps inherent in the interdisciplinary nature of food systems work — was the unexpected twists and turns many panels took. In this one, we spent quite a bit of time discussing language. Why is it that migrant farm workers in Europe are not referred to as farmers, despite the fact they work the land and hold valuable knowledge about doing so?4 Why do we call ourselves the “alternative” farming movement, when in fact, we could take a leaf from the conference’s book and brand ourselves as the “real” farming movement? Would that help to legitimize and emphasize agroecology — or rather detract from momentum by erasing the movement’s radical, “outsider” position?

Speaker Sophia Doyle also made some fascinating points on how the agroecology movement, by articulating its demands through the language of citizenship and bureaucracy of the state, is reinforcing and legitimizing the hegemony of racist-neocolonial state power (at whose borders in Europe, for example, an average of five migrants die every day).5

Further resources:

‘Trading Away the Future? How the EU’s agri-food policy is at odds with sustainability goals’, Feedback EU (researched and written by me!)

What I wished I could have also attended: Radical Honesty in Action: Paving the Way for Food and Racial Justice (Speakers: Roshni Shah, Nicola Scott, Dawn Dublin / Chair: Idman Abdurahaman)

What I attended: Eating and Shaping the World: Writing New Narratives (Facilitators: Carmen Posada Monroy, Charlotte Dufour)

This workshop was an interactive session focused on creating new narratives for understanding, conceiving, and reshaping food systems. As co-facilitator Carmen Posa Monroy noted, “narratives shape the world”, and define how we should feed it — something we think about a lot at FFJ. How can we use narratives to define what is normal, and to move that normal away from heavily industrialized agriculture?

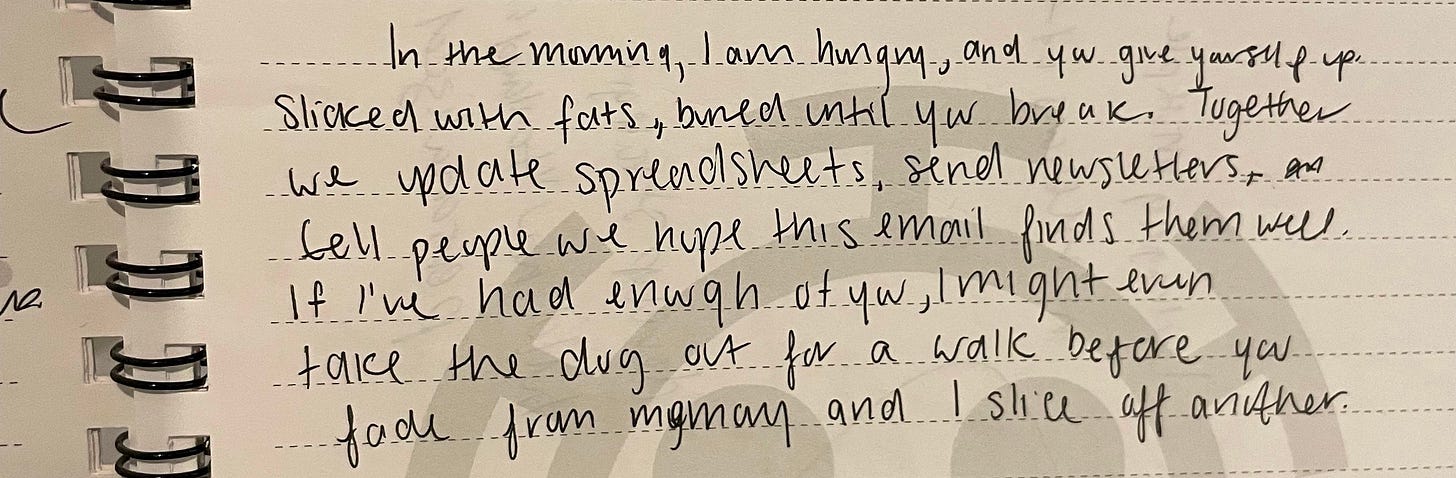

To guide us through our thinking on this, the facilitators had us choose one part of our more-than-human ecological web to focus on; my group chose wheat. We then were tasked with writing “letters of gratitude” to our being of choice, and finding common ground in our letters to craft a narrative using prompts from the “Eating and Shaping the World — Conscious Food Systems Guide.” While my group got productively sidetracked introducing ourselves, our work, and our dietary intolerances, I managed to get a few sentences down. It is more a reflection on the ubiquity of wheat as bread, how it’s just always there, and how despite my stereotypical pandemic-era obsession with sourdough, I don’t often stop to appreciate it:

As a group, we agreed that our new narrative on wheat would focus on repairing our relationship with it, done in three catchy steps: apologize, democratize, idolize. We must first apologize to wheat for altering its molecular structure without its consent, as well as repair the harms done to Indigenous and Global South communities in the name of wheat monocultures; we must then bring bread back to the people (not just yuppies like me baking sourdough for two months) through the simplicity of its ingredients, and finally, we must also recenter wheat in our celebrations. After all, what is conviviality without the breaking of bread? If we’d had enough time, I would’ve loved to translate this three-step program into a short poem or story.

Further resources:

Eating and Shaping the World — Conscious Food Systems Guide, convened by UNDP

AFTERNOON

What I attended: The Rise of the Planet of the Chicken (Speaker: Diane Purkiss / Chair: Tamsin Blaxter)

Chaired by TABLE’s Tamsin Blaxter (who wrote an excellent piece for our MEAT issue), this might have just been my favourite session of the conference. Food historian and literature professor Diane Purkiss had the audience enraptured — I wish I could sit in one of her lectures — by an anecdote about a childhood pet chicken who never recovered from having her eggs harvested. She then narrated a fascinating history of how chicken went from a “weekend treat” to a profane weekday meal in the course of just a few decades. She also highlighted that white “breast” meat has long been seen as something “for” women, perhaps due to the now outdated and inaccurate myth that breast meat is lean (in actuality, she says that breast meat has become 150% fattier since World War II). I scrambled to record Purkiss’ answer to an audience question on the gendered dimensions of chicken-eating, which you can listen to here:

A really interesting part of this conversation was Purkiss’ argument that while we may feel powerless in the face of the seemingly entrenched industrial food system, food cultures can actually change very fast (as the broiler chicken boom evidences). In Purkiss’ words: “That is both a bad and a hopeful thing.”6

Though it is not directly related to chicken, I was fascinated by Purkiss’ recounting of the trials of recreating recipes from antiquity and the Middle Ages. At the time, instructions were barebones (to say the least: she recounted one instruction along the lines of “take a goose and add flour, enough”) and most of our contemporary ingredients have radically changed (including flour, which has far more protein content today than it did in Shakespeare’s times).

Further resources:

What I attended: Transition to Agroecology — What Role Does Ecocide Law Play (Speakers: Jojo Mehta, Martin Lines, Rob Percival / Chair: Sarah Langford)

I’ll be honest here — by this point, my attention was flagging. Tamsin from TABLE and I had tried to attend a session on the sentience of insects and what this means for the future of food (Tamsin has done some amazing work on animal welfare and ethics) but it was too full by the time we arrived from her Planet Chicken panel. Instead, we managed to get into this one about 10 minutes late. Panelists Jojo Mehta, Martin Lines, and Rob Percival discussed the possibilities of a new ecocide law put to the International Criminal Court, whose draft wording reads:

This pioneering international law is not designed to catch every environmental harm everywhere but rather to define the parameters by which ecocide can be understood and to promote the use of national laws to prosecute it.7 While organizations involved expected that they’d need to campaign aggressively to receive public buy-in, a recent survey found that 72% of people in G20 countries believe that ecocide should be a crime.

Thanks to an audience question, I learned that criminal laws — including this one proposed on ecocide — are purposefully worded vaguely so that crimes can be situated in context and to limit loopholes. In the words of Mehta, “If someone attacked me, their crime wouldn’t be conditional on the amount of bruises that I have”; similarly, using terms like “widespread” and “long-term” harm ensures that perpetrators can’t get off the hook for polluting 17 kilometres of a river rather than 18.

The same audience member who noted in the fascism session on Thursday that green transitions are also embedded with forms of neocolonial extraction raised the point again and also highlighted how speakers from the Global South were underrepresented at the event. This was completely true and is both a symptom of geographic location8 and the power inequalities that remain very much present in food systems decision-making. (Hence why I wish I could’ve attended the session on racial justice in food systems change!)

Further resources:

What I wish I could have also attended: What Might Insect Sentience Mean for the Future of Agroecology? (Speakers: Andrew Crump, Vicki Hird, Cristina Amaro da Costa . Chair: Natacha Rossi, Beth Nicholls)

As mentioned, the session was sadly full — so I’ve made do with this article published last week in the New Yorker. A lot to think about there.

That’s all for now! Get in touch (by email or comment) if you’d like to discuss any of these topics further, or have any questions about the conference. As mentioned, I’d be happy to organize a call with any premium subscribers.

— IJbV

ORFC offers extremely affordable online tickets, so if you missed out this year, don’t sleep on it for 2026. Sign up for their newsletter to be the first to hear about tickets.

While I was too busy to eat much of note in Oxford, I did have the chance to dine at the iconic St. John with friends in London the night before the conference, and I’ll be dreaming about that ox tongue pie for a long time.

Ramdas also talked about the gendered ways that the caste system is used to uphold capitalism, by ensuring that Dalit and Adivasi are forced to sell their labour, reminding me of three pieces we’ve published on gender and caste in Feminist Food Journal: Breaking Coconuts, A Fistful of Salt, and Respectable Lives and Transgressive Tastes.

This is something I have thought about quite a bit in my PhD research, which looks at how immigrants are framed within urban food systems change. Who gets to be called a “farmer” and why?

I touch on this issue briefly in relation to food citizenship in my recently published academic article from my PhD research (see pg. 5 in the PDF) and agree that Doyle’s assessment raises urgent questions about how we can redefine what constitutes “sovereign” beyond relationships to state power.

The power for us to shift our food cultures was the subject of the book Mobilize Food! Wartime Inspiration for Environmental Victory Today by Eleanor Boyle, which looks at how the UK’s food system transformed rapidly during WWII through a whole-of-society effort. Eleanor wrote for us in 2022.

According to panellists privy to the law’s drafting process, countries in Africa and Latin America are hoping to use it to hold extractive foreign companies to account (an important connection to the Friday morning session I attended about imperialist trade frameworks).

It felt like an immense effort even for me to get to Oxford just from Barcelona, and I have the additional privilege of visa-free access to the UK!