Editor’s note: Amidst the backdrop of a sham “ceasefire” in Gaza and the shock of violence that the first weeks of 2026 have brought, the news of ICE executing yet another human being is almost too much to bear. Feminist Food Journal has no ties to the US, but like many of you, we are deeply moved by the solidarity and organizing that is coming out of Minnesota, and encourage you to support legal aid and mutual aid funds if it is within your means. Today’s essay by Nina Katz also makes excellent reading on how we can continue to build resilient communities in the face of cruelty and attempted erasure.

Queer communities in North America have uniquely embraced potlucking throughout history as a means of celebrating the goings-on of their lives. But potlucking, as a way of eating together, is a celebration of queerness itself.

By Nina Katz for our CELEBRATE issue | Editing supported by Apoorva Sripathi (who has also illustrated this piece and the remainder of the CELEBRATE issue!)

Premium subscribers have access to an audio reading of this essay by the author.

I was in college when I went to my first potluck. It was during the fall semester, following a morning of volunteer work pulling weeds at the community farm on campus. The email to volunteers had asked us to bring a dish; so when the farm work was done for the day, we all gathered at a picnic table beneath a large gingko tree to eat.

Potlucks are supposed to have originated in sixteenth-century Europe.1 The word originally meant no more than “taking your chances with whatever was available from the pot on the fire.” Having now evolved to signify communal meals where participants bring food or beverages to share, especially in North America, potlucks tend to pop up in times and places where sharing is caring — and this one under the gingko tree was no exception.

I was a sophomore without a kitchen, so I brought chips and salsa purchased at the student center using dining points. But older students who lived in the sought-after housing with kitchens brought fresh zucchini bread, pasta salad, and baked squash with a sticky, sweet nut topping. It was the first time in weeks I’d eaten anything homemade.

The year of my first potluck was also the year I came out, professing my love to a girl on a walk through the woods around campus. At the time, I didn’t yet know that food and sharing meals would eventually become an indicator of feeling full in my queer life, nor that potlucks — which allow me to draw on a long politicized history with the radical potential to build a better world — would be the main source of much of that fullness.

I remember the first time I saw a group of lesbians in public: I was seven or eight years old with my parents and brother at a seafood shack in Provincetown, Massachusetts, which I was, of course, unaware was also a port for gays. I was downing a bowl of clam chowder after a day of whale watching when I noticed a group of four women with boyish clothes and hair at a table next to ours. The way they sat in pairs, closely nestled into each other, caught my attention. It is one of my most vibrant memories of noticing queerness as a child, and the memory is accompanied by the sound of crunching oyster crackers and the smell of boiled red lobster. Perhaps this was one of my earliest memories of food and queerness, which for me are deeply intertwined.

In my early years of college, just after the potluck, I was still learning the basics of cooking. I seemed to have inherited my parents’ penchant for dinner party perfection: a balanced taste for both delicacies and heirloom family recipes, but also an obsession with getting it right, knowing no greater satisfaction in life than cooking something that makes someone else say, “Oh my god, that is so good.” If I were hosting dinner, why would I let anyone else do the work when I derived such joy from being in control of the meal? As I became more adept in the kitchen, food quickly became my way of making meaning of my queer life: taking food over to a friend who just had top surgery, or throwing big fundraising parties featuring soups made by queer chefs as the organizer of my local chapter of Queer Soup Night.

In my early explorations in a kitchen of my own, I was bridging my queerness with my love of food, though at first, I wasn’t thinking about it. Still in college, when I was living in an entirely queer house, my roommates and I invited our favourite professors from the philosophy and religious studies departments to dinner using a haggadah from the organization Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (a bit different from the Maxwell House haggadahs I grew up with).

We made roasted carrots instead of the traditional brisket, an ode to the previous semester’s class on ecofeminism. This dinner was a coming-of-age, where food allowed us to take ownership of traditions that had always been special and to make them part of our queer adulthoods. But it was through potlucking that I was introduced to yet another kind of tradition: one where I didn’t have full control over the kitchen, and that was the point. Potlucks, like the first one I experienced under the ginkgo tree, expanded the potential I saw in communal eating, one that would later be reinforced by my research on queer potlucking history.

Potlucks, though not necessarily an invention of queer people, have been so embraced by queer communities in the US since the mid-twentieth century that to me, potlucking is queer itself. Throughout history, potlucks have been a way for queer people to use cooking, food, and sharing meals to make meaning of their lives. The potluck has not only allowed queer people to join together in the face of loneliness or exile, but find identity and joy in the partaking of a meal that in many ways reflects what feels liberatory about being queer in the first place. Just as being queer can mean the rejection of heteronormative hierarchies, the potluck often feels like a rejection of domestic conventions that can reinforce rigidity in eating together.

Potlucking was my entry point to understanding how performance, rituals, and experimentation with food can be a means of forging a queer life, a way to taste queer histories, and, by design, a way to be in community. Craft nights, mutual aid fundraisers, community meetings, birthday parties, memorials, weddings — no matter the occasion, it can be potlucked.

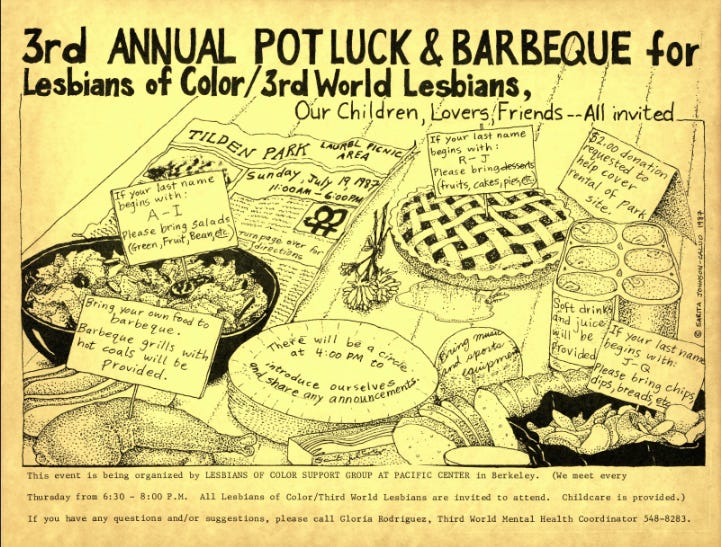

While researching queerness and food for my Master’s in Food Studies, I dove deep into the queer archives2 for any glimpses of gay food culture. I began noticing the recurrence of potluck flyers published in the final quarter of the millennium. A 1983 issue of Onyx: Black Lesbian Newsletter said to “call Midgett or Billy for the address” of the bi-monthly Bay Area Black Lesbians and Gays soul food potlucks. A November 1990 issue of Gay Community News advertised three totally separate potlucks in their community calendar.

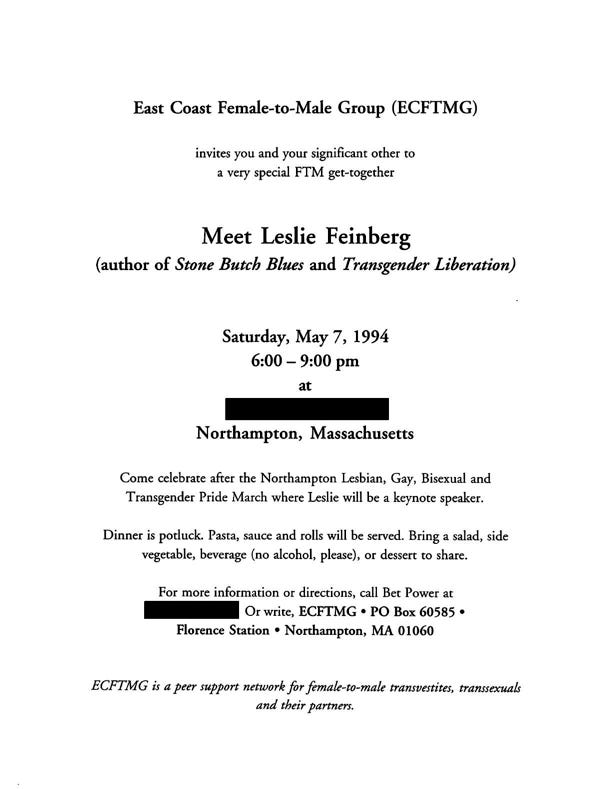

One potluck flyer stood out. In simple, black and white print, it read that on Saturday, May 7th, 1994, the East Coast Female-to-Male Group (ECFTMG) hosted a “very special FTM get-together” at the Western Massachusetts home of the Sexual Minorities Archives for a meet-and-greet and dinner with transgender activist and author Leslie Feinberg. The occasion was the afterparty for the Northampton LGBT Pride March, where Feinberg was the keynote speaker. “Come celebrate… Dinner is potluck,” the flyer read.

This potluck took place less than a year after the release of Feinberg’s groundbreaking autofiction Stone Butch Blues, a rightful cult classic (that happens to contain a lot of excellent food writing focused on the communal aspects of lesbian working-class life). When I came across the flyer 30 years later, I found that it stirred within me a nostalgia for a time I never experienced. Blues was a book that I had first read cover-to-cover a few years earlier. Upon finishing it, I immediately flipped back to the first page and started it over again.

When I saw the 1994 flyer, I couldn’t help but wonder what Feinberg had brought to the potluck — or indeed, what everyone had brought. I imagined a table full of food, with every dish representing some part of each attendee’s life, and it made me feel a bit closer to queer generations that came before me. Holding these flyers and imagining the shared meals made me yearn for a taste of these queer pasts.

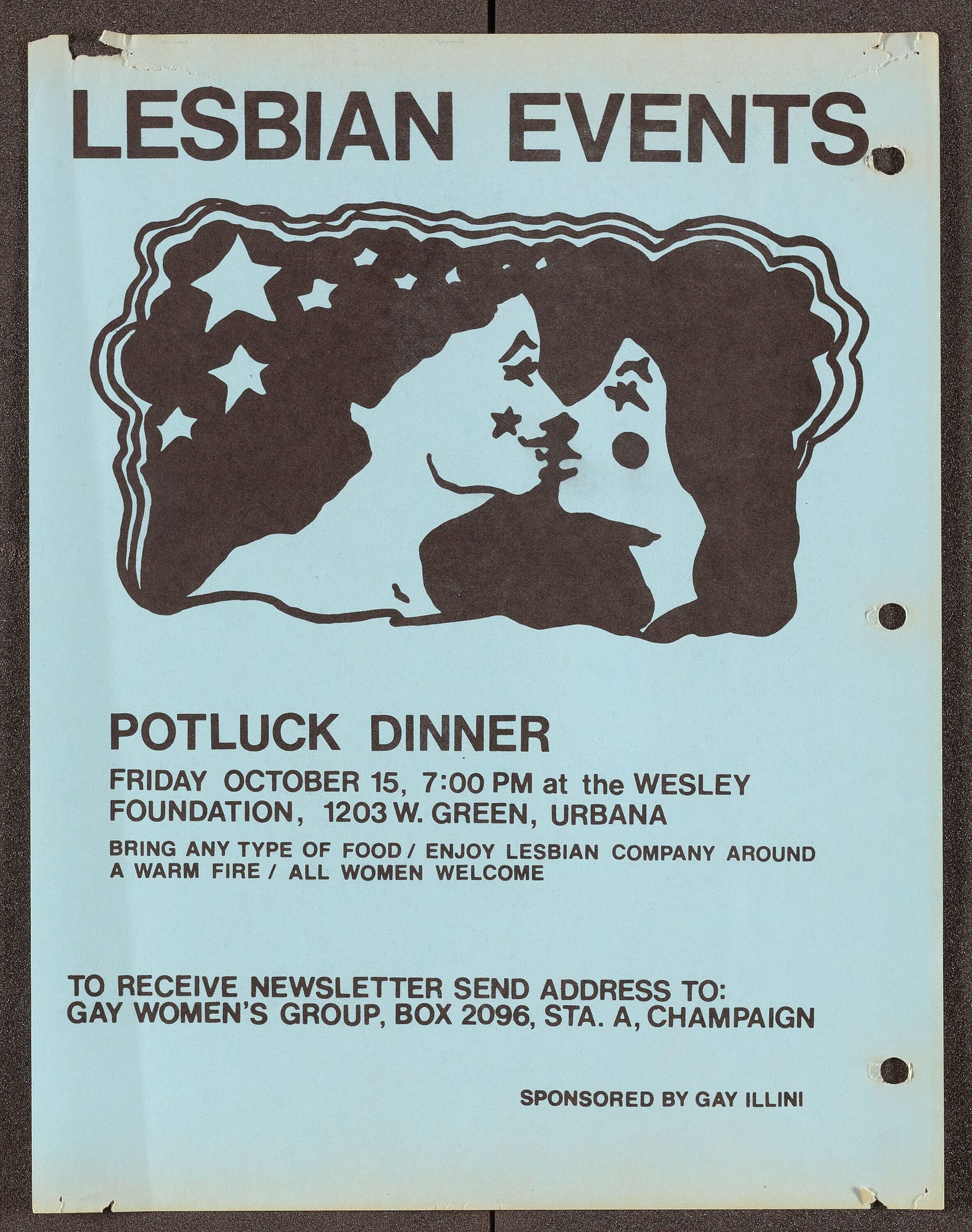

Much potluck talk in the queer discourse refers to potlucks held by and for lesbians — also known as lesbian potlucks. Though it’s hard to imagine a queer history that didn’t include gathering around a meal, The Daughters of Bilitis, the first known lesbian civil rights and political organization in the US, is credited with that first stab at an organized queering of the potluck in the 1950s. While queer people often felt rejected from the church communities or family reunions where potlucks or covered-dish suppers really got their start in America, this meal of the commons was swiftly adopted as a covert and nourishing get-together by lesbian communities across the country.34

In A Queer New York, Jen Jack Gieseking affirms this omnipresence by suggesting that lesbians are “often [narrowly] associated with what [they call] a rhetoric of potlucks and protests,” however, “the actuality of everyday lesbian-queer life is, obviously, more complicated.” But so too are potlucks. Just like any social gathering, potlucks are not necessarily always as peaceful and harmonious as one might idealize them to be — they can also include stirred-up drama, inedible goop, or difficult confrontations.

Nothing exemplifies this more than the auto-fictional characters in Cheryl Dunye’s 1993 short experimental film The Potluck and the Passion, which leverages food and the dynamics of sharing a meal at a potluck to highlight race and class differences in an urban American lesbian community.5 The tensions that unfold throughout the film are foreshadowed at the beginning, when one of the hosts worries that the guests, who include some friends and some tag-alongs, “might not get along because they are from different schools, different worlds.”

Throughout the meal, superiority complexes, nefarious flirtations, and microaggressions are all on display. This isn’t exactly the egalitarian dinner party laid out by some potluck theorists,6 and yet, the meal is still democratized — it is a space for queer people to come together and create a shared meal that is their own.

The flyers stayed with me, and were the nudge I finally needed to become a potluck host myself. The first occurred at the 100-year-old house on a hill. I was sharing a lease with two friends, one elderly chihuahua-Jack Russel Terrier mix, and a neighbour’s cat we let hang out in our living room most days. The house overlooked our beloved Pittsburgh, and thus we named our potlucks “Pittlucks” and set out extra card tables in our living room for friends, exes, and lovers to place blueberry cheesecake bars, charcuterie, focaccia, cauliflower gratin, gloppy noodle salads, and gluten-free Double Stuf Oreos.

Potlucking connects us with queer ancestors whom we’ve been barred from knowing; beyond the snippets I find in the archives, so much of queer history goes undocumented. At the potluck, I feel their lives layered into my own.

My potlucking practice hit its height in 2022, when this friend group of mine in Pittsburgh potlucked monthly. We started at my house, then rotated to someone else’s; over time, we all took turns hosting. New faces would pop up each time: a friend of a friend new in town from Ohio, Sonny’s mom, who was visiting for the weekend from Massachusetts, Emily’s new co-worker, the person who stood next to Vinny at last night’s concert, Eve’s regular at the coffee shop. At the queer potluck, you look around at a room full of people you may not know, and yet know that they are your people — that when your rights are threatened, when the world feels like a less safe place to be yourself, these are the people you can turn to, who celebrate your identity.

This is not to say that conflict does not happen in a room full of queer people eating casserole. Though there is potential for real harm, conflict can also lead to change that is good and constructive. As Dunye portrayed in Passion, conflict over food and ways of eating together causes real shifts in the character’s perspectives. Last summer, I experienced queer potluck conflict at a daytime Pride event with some friends on the patio of a restaurant in Old Town Albuquerque, about a fifteen-minute drive from where I now live. Rainbow flags swayed in the breeze as we sipped iced teas, listening to a local band sing about revolution on a pallet stage. At one point, I looked up to see an older, Gen X woman standing at our table, asking me if I was the Nina who throws potlucks. “Yes!” I responded, always excited to connect over something food-related.

“Nice to meet you. What are your pronouns?” she continued.

“They/them,” I replied. “Yours?”

“She/her. And, well, unfortunately, you can’t come to my potluck. It’s only for lesbians.”

Damn, I thought she was asking my pronouns to be cool, not to size me up.

“But I am a lesbian,” I retorted, my two friends’ eyes widening.

“Interesting! I’d love to talk more about that,” she replied.

There was an empty chair at our table, but instead of taking a seat and engaging me in conversation about generational shifts around gender identity in the 21st century, she picked up the chair and walked it back to her table.

This, as with most of my encounters with lesbian separatism, left me with complicated feelings. I think affinity spaces are good. But I do not like assumptions made about which affinity spaces others belong to. The interaction may have temporarily dampened my mood, but in that moment, my feeling that potlucks are representative of a queer ethic felt more alive than ever.

Had she not stolen our chair and rather sat down with us, I could have laid out my understanding of the potluck to problematize her exclusionary tactic. I would have made my case that, as a meal that lacks hierarchical norms and embraces difference, potlucks teach us that attempting to essentialize what it means to be a lesbian is an impossible feat.

As enriching as potlucks have been for queer communities over time, I cannot help but draw connections between queers at potlucks and the queerness of potlucks. I do not mean to oversimplify queer realities, but to offer the potluck as a playground for a conscious exploration of queer values.

Potlucking has helped me grow as a community member, and has provided me with a space to evolve away from the patriarchal norms that feminist and queer theories orient away from: it has helped me reject hierarchical and binary thinking and to challenge norms like the one that dictates that a dinner party must be ruled by a host/guest dynamic or gendered and heteronormative expectations on the labour of organizing a dinner party. Potlucks have helped me explore queer kinship or “chosen family,” embrace fluidity, and value difference. So much so that the potluck itself is a celebration of the values many queer people strive towards, and perhaps manifest, in these occasions of eating together.

At a birthday potluck for my friend Olive, as we finished up the food, we pushed back her blue velvet couch to make room for dancing. Olive’s black cat slept curled up on a throw pillow, her tail twitching. I found a seat beside her to quickly rest my legs. I smiled at the group taking up the rest of the room. Fearless, exuberant queerness all around. I sang along to the lyrics7 playing from the speaker:

If it feels good to me

It feels good to me

Ooh why couldn’t it be?

Ooh why wouldn’t it be?

I jumped up for the chorus, singing along as loud as I possibly could, electrified by the energy of my fellow potluckers, radically baring our queerness. When the song ended, the room exhaled. Ruby ran into the other room and returned with her homemade blueberry focaccia. We caught our breath between bites of the bread.

“So, who’s hosting the next one?” Olive asked the group.

Nina Katz (they/them) is a writer and educator based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they are the chapter lead of Queer Soup Night New Mexico and constantly begging their friends to join them for fro-yo. @ninatummyache

The alleged origin of the “potluck” can be found within the dictionary Food (2000), wherein author Robert A. Palmatier traces the term back to the Middle Ages, in Europe, where travellers would come across a pub and, for dinner, “take luck in the pot,” eating whatever was boiling above the hearth. The first written record of the term appeared in 1592, penned into the lines of a play by poet Thomas Nash. The line in which the term appears reads, “That that pure sanguine complexion of yours may never be famisht with pot luck.” Palmatier then states that by the late 19th century, “potluck” had evolved from a verb to a noun due to the popularization of “potluck suppers,” which carry forth the surprise-me element of taking potluck.

Some of my favourite North American queer archives to research with are the Jean Nikolaus Tretter Collections at the University of Minnesota, the Transgender Digital Archives, the Bay Area Lesbian Archives, and the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

In 2019, journalist and researcher Reina Gattuso’s essay “How Lesbian Potlucks Nourished the LGBTQ Movement” describes how queer community adopted the American tradition of potlucking as a means to covertly and safely gather.

Potlucks have existed beyond just lesbian communities, at many intersections of queerness, for example, at the aforementioned 1994 ECFTMG Pride event. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a leading force in AIDS research, prevention, and organizing, had its humble beginnings in a series of potlucks hosted for grieving community members. In an essay for the anthology “Activist: Portraits of Courage” (2019), edited by KK Ottesen, ACT UP co-founder Avram Finkelstein writes of his motivation to gather with his grieving community of fellow gay men. Finkelstein recounts the weekly potluck dinners as a space where the collective could talk, cry, and fight, “putting one foot in front of the other” (249). Admittedly, even though these early meetings were made up of primarily gay men, it’s been said that the group referred to their dinners not as potlucks, but as “lesbian potlucks.”

Liberian American Cheryl Dunye, the first out Black lesbian filmmaker to make a feature film in the US, wrote and directed “The Potluck and the Passion” (1993).

In Performing Action (2000), American sociologist Joseph Gusfield argues that “no one is in charge at a potluck.” Gusfield asserts that the potluck really can be a total “release from the role-playing and self-consciousness and regulation of organizational existence” that is engendered, in comparison, by the structured dinner party, like the ones my parents hosted as I was growing up. However, I want to push back on Gusfield’s repeated use of the word “formal” to contrast the structured meal to the potluck. I find that implying that formality based on normativity (coming from a White cis-male and hetero academic) does not occur at the potluck limits our understanding of what meanings inscribed through food practices can be considered legitimate or important. I find that this also implies that diffused labour = less labour, while my experiences leading up to the potlucks I host and attend suggest that diffused labour = labour made visible.

The song “I Know A Place” by the band MUNA was written in 2015, days after gay marriage became legalized by the Supreme Court in all 50 states, and was still being produced when a year later, 49 people were massacred, and 53 more were injured at the Pulse nightclub in Miami, Florida. Written to be a pride rallying cry, my friends and I found ourselves dancing or just humming along to this song at almost every potluck.

The word comes from the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest coast; "potlatch" meaning "to give away" or "a gift". They are still here.

Thank you for sharing these stories of potlucks and queerness, a world here in the UK I would love to learn more about and I might even host my own making sure everyone has a seat at the table.