In April, FFJ editor Isabela Bonnevera (née: Vera) found out that her family’s earliest-known ancestor may have been born in an eponymous town in the south of Spain. The 600-kilometre trip down from Barcelona proved to be a pilgrimage of sorts, a reckoning with family relationships and identities as they are and as we wish them to be.

By Isabela Bonnevera | Paid subscribers can listen to an audio reading of this piece on our podcast.

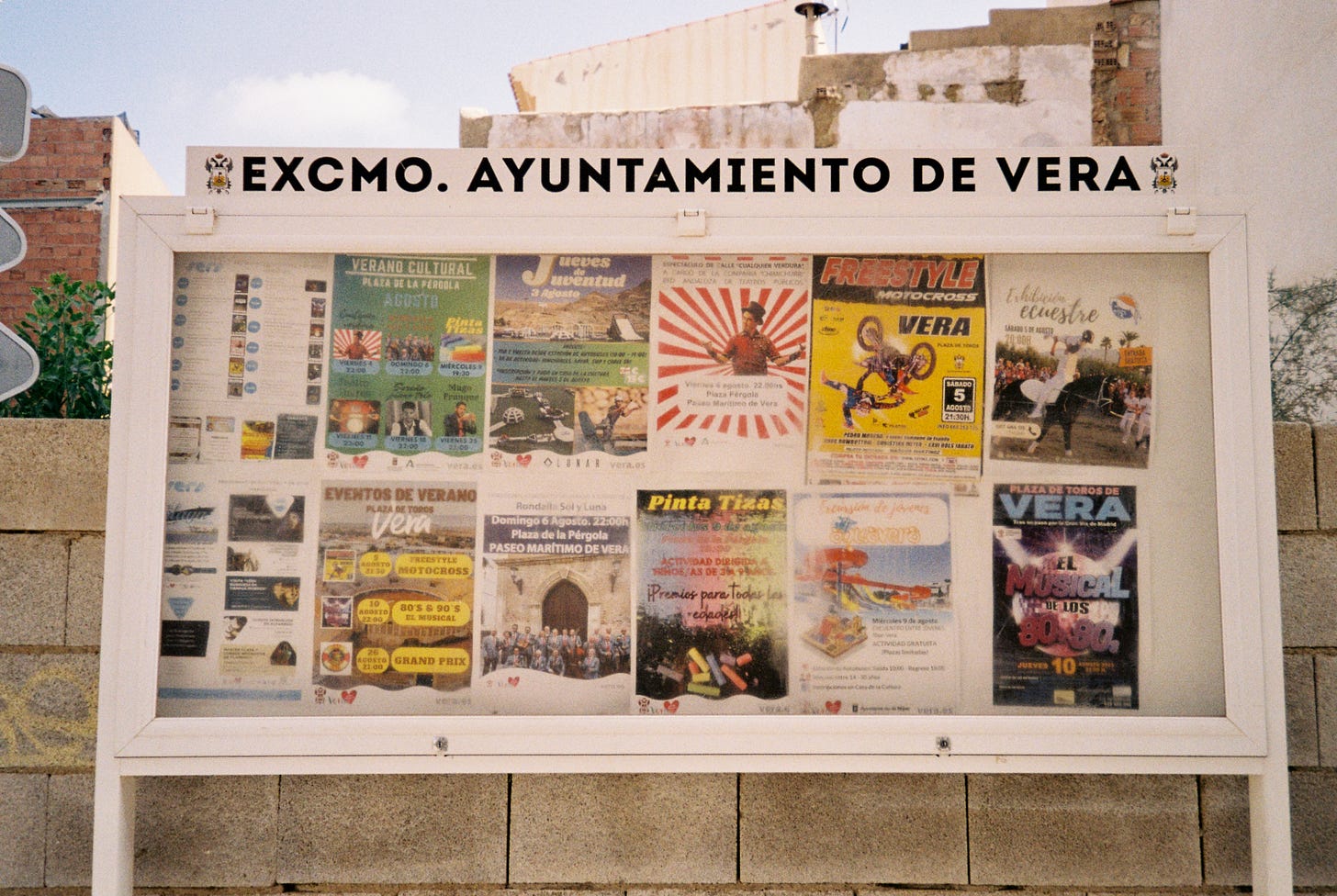

My much-awaited first meal in the town of Vera, known locally as Vera Pueblo, wasn’t even in the town itself. It was just under ten kilometres away at Vera Playa, a seaside resort also known as Europe’s largest nudist colony. When we pulled into the town earlier that day, after a short car ride from Granada and under the cast of the golden late afternoon sun, it had felt largely abandoned. Whether that was because it was a Sunday or just the middle of August, I wasn’t quite sure. There were a few signs of life; announcement boards plastered in flyers for music nights and heritage walks, church bells ringing at 7 p.m. with a few diehards filing in for mass. But we couldn’t find anywhere to eat aside from a kebab shop, and so to the more animated playa for dinner we went.

The beach bar we chose was bustling, the belly button of place; Believe by Cher pumped from the stereo as teams of naked, hairless volleyball players dove around nearby, their glistening bodies slick with tanning oil that soon picked up zebra stripes of sticky sand. I ordered a Caesar salad only to find the emperor’s tang sorely missing, a tasteless lump of mayonnaise dumped in its stead. I was already bloated and greasy in the 40-degree heat; the impulse to order something so creamy immediately felt like a mistake. But I had fantasized so much about this trip that it seemed silly to let a bad meal or imminent indigestion spoil the mood, so I focused on sipping my tinto de verano, narrowing my eyes in the hazy evening light to people-watch. There were no tourists; the only foreigners seemed to be people who had bought the nouveau-California-like developments along the coastline.

By dusk, grey clouds fat with the threat of rain had started colliding. Eager to escape them and my half-eaten salad, we drove home to our hotel. I made my partner promise to get up early to visit the town’s museum even though I knew there was no way we would be awake before 10 a.m. The museum was the real reason we had come, to this town that shares my family name.

When we stumbled into the museum around noon, its sole employee was collecting data on visitors. Where were we from, how long were we staying? Dos noches, I told him, flashing a peace sign in case my accent was unintelligible. Fielding that question was easy enough. But describing where I came from felt a bit like unravelling a roll of string. You can put me down as Canadian, I said, but we live not so far away, in Barcelona. And I think I have an ancestor who came from this town, whose son then sailed to Chile, a few hundred years before my grandparents moved to Canada.

Verdad? He was suddenly animated. Sabes su nombre? Do you know his name?

***

Jeronimo de Vera was born in 1607. His son, Bartolome Vera Velasquez, was born in 1635 in Seville but died in 1690 in Santiago, Chile, making him our first ancestor in what is now commonly referred to as the Americas.

This is relatively new information for me. A few months before visiting Vera, I had received an email from my paternal grandfather to let us know that his nephew recently completed our family tree using the Ancestry App. It presented the following lineage:

On the list’s oldest name, my grandfather quickly sent one additional follow-up:

In the case of Jeronimo de Vera is interesting to observe that by 1600 in Europe it was usual to have the first name only and the second name referred to the city of origin, For Example Leonardo Da Vinci was Leonardo who came from Vinci a small Italian town. In Andalucia, Spain, there is a small town Vera, so Jeronimo probably was born there.

-JHV

I was intrigued. Until then, I had known much more about my ancestors on my paternal grandmother’s side. They left for Chile at the turn of the 19th century, an era of industry, machine, and noxious smoke on the horizon that was easy enough to imagine. But the birth of Jeronimo in Vera in 1607 felt harder to conjure, as did the voyage made by Jeronimo’s son, Bartolome, to Santiago sometime in the next decades.

Having moved to Spain just seven months before my grandfather’s revelation, I quickly decided that I wanted to visit Vera for myself; anything less would be a slap in the face to these long-departed, little-known ancestors whose faces and stories faded across the seas. (Also, a quick Google search revealed that Vera Playa holds the Guinness World Record for “Largest Skinny Dip”; after reading that, the trip was all but sold to the highest bidder.) It was late spring, and everyone said we shouldn’t go to Andalusia in the summertime, but of course, I booked tickets to go during our next available vacation slot in August. We flew first to Granada and after a few days of sweating across the Alhambra, we rented a car to get to this town to which I had no prior connection beyond a diagram provided by the world’s largest for-profit genealogy company.

As soon as the signs for “Vera” started appearing on the highway — 60 km to go, then 16 — I was overcome by a sense of connection to the place, tiny magnets in my skin tingling with anticipation of the upcoming thud of reunion. But anyone who watched the plight of the Di Grasso family in season 2 of The White Lotus knows that expecting a warm welcome from distant European relatives is folly. I was already aware of my own overbearing North Americanness in sending an extremely detailed booking request to the town’s only hotel back in April. (They replied something along the lines of “Señora, we don’t care about your ancestor, but we do have a room available.”) I kept mum about my family history as we slid our passports across the check-in desk. But my sunburned cheeks fell when the receptionist didn’t comment on the serendipitous matching of names, and my behaviour probably did appear slightly peculiar. I wanted to absorb every detail of the place, remember the thick, faintly cheesy smell in each breath taken around the glistening legs of jamón dangling from the hotel restaurant’s ceiling. The hotel had walls lined with promotional posters for bullfights gone by and I took photos of them from every possible angle. I told my partner that we were living the Andalusian dream.

***

I’m fascinated by long-standing cultural traditions like bullfighting and curing ham, probably because I didn’t grow up with many. My father was born to a formally baptized but relatively secular family in Chile, and my mom to an overtly atheist Jewish one in Montréal. We lived in Vancouver, far away from more pious Jewish relatives on the East Coast and even further from Chilean ones way down south. No teacher ever called out my name on attendance lists for Saturday School or Hebrew lessons. My mom came into my elementary school to make latkes for a few token Hannukah events, but otherwise, our main family food ritual was to go for Cantonese on rainy Sunday nights.

We also made up new traditions at home. Back when I was shorter than the kitchen table, my mother worked on Sunday nights as a server at a seafood restaurant in East Vancouver. Those nights, my dad would be in charge of dinner. His specialty was Toxic Tofu — marinated tofu steaks fried to a crisp. These remain top of his repertoire to this day, along with frozen burritos and hard-boiled eggs, made in a six-hole egg cooker that announces their readiness with a whine.

A propensity for cooking simple meals. Here lies one intersection of our myriad similarities: a Venn diagram with a bulging middle that has, somehow, never seemed to be able to compensate for a few antipodes on the peripheries. I’ve become much more inspired in the kitchen, but for much of my life, if left to my own devices I ate much the same as my dad does now. Chickpeas from a can onto some spinach; peanut butter straight from the jar onto a rice cake. Even Bartolome Vera and his 15th-century seamen might have turned their scurvy-white noses up my (ahead of their time) girl dinners. It is always a battle of taste versus convenience; such rapid-fire foods lend themselves to my incessant puttering. If I’m eating alone, I’m immediately distracted by a million things in the house calling out for me to attend to. Eat with one hand, rearrange cutlery drawer with the other. My dad is like this, too. When we watch TV shows, he is always working on something else — laying out fishing rods, tying flies, repairing waders. “So she’s leaving him for his uncle?” he’ll ask at the conclusion of a pivotal scene, looking up from tying an intricate knot. “No, she’s asking his uncle for his blessing,” my mom and I will reply in unison, if I haven’t been scrolling through my phone too compulsively to keep up.

After a few evenings of tinkering in front of the TV, my dad will pack up his gear and head out to the water. He’ll either go on foot into a river, wrapped in waders, or to the local estuary in a small boat he stores in the garage. Some days the catch is good, the water hopping like popcorn with mouths that can’t wait to impale themselves. On others, the surface stays as impenetrable and smooth as glass. In my younger years, I was limited to catch-and-release outings for my refusal to club (or be present for the clubbing of) any creatures we brought up to the boat or the shore. These years coincided with my dad buying me a collection of books by Dave Barry, a humorist who has one recurring schtick on how the fish you need to kill are always painfully cute — something along the lines of them blinking up at you in a way you could imagine rendered on a cover of a children’s book called Billy Bluegill Learns The True Meaning of Christmas.

Given that I now live so far away, my dad’s motorboat is only a prop on summer holidays, when we’re out in the beating hot sun to fish or catch crab. I’ve grown the stomach to close my eyes during the final moments of aquatic vertebrates, and on occasion, I even get to steer the boat. But I still can’t bring myself to kill any fish. Instead, I run my hands through the cold salty water and dream of how refreshing it would feel to dive in, if not for the deadly currents. I feel that every moment spent on the boat with my dad is precious. Fishing is neutral ground, something we can share without controversy. Once I’m away, with oceans of distance between us, our communication historically dries up.

I know I should call my dad more often. My whole life, he’s been infallibly present. After dinner, on the Sundays my mom was working, he’d turn the lights off in the living room and lead us to dance around in the dark to the B-52s. Later, weekends that could’ve been spent wrestling salmon on the shore of a wild river instead unfolded on the sidelines of what must have been painfully mediocre soccer games, cheering for hours before patiently loading muddy teammates into the green family minivan to carpool them home. He taught me how to throw a football, helped me master algebra, and bought us computer games designed to hone our critical thinking skills. When I was 21 and started my first summer desk job across town, I no longer had my own car. My dad would load my bicycle into his hatchback in the mornings and detour from his usual route to work to spare me a roundtrip commute on body-powered wheels. To this day, there remains no problem that he won’t help me solve.

But our ways of relating to each other more deeply have always seemed to clash; attempts to connect, tragically misunderstood. 20 years of conflict have left us tip-toeing over cracked ground. Our conversations are cordial, but clipped. I sometimes hear myself use a voice normally reserved for customer service situations. There’s a mutual understanding that the peace we share is fragile. I know I should call him more often, yet an instinctive impulse holds me back, fear that an attempt to reach out may end up rocking the boat.

And so I go looking for clues, context and places that help me to feel closer to my father and his life. Vera Town is one such place; so is his birth country, Chile. My grandmother still spends part of the year there, and I’m trying to forge better-late-than-never connections with other relatives, which isn’t straightforward when you have a shaky grip on the language and a limited understanding of the culture. A few second cousins are my age, and I’m mortified when we have to switch to English to converse meaningfully.

Beyond confusing ser and estar, I fear that I’m getting the chance to know and love some of the people in Chile later than life would’ve liked. A great uncle in Santiago with whom I’ve spent quite a bit of time on my trips and feel particularly close to has cancer; the prognosis is unclear, not due to medical failures but rather the (I suspect purposefully) vague language that my grandmother uses when talking about it. On my grandfather's side of the family, a few relatives who remember my dad as a child seem to be in poor health, but they beam as they welcome us into their homes with plates of empanadas, as if we were old friends and not meeting for only the first or second time. As we eat together, I listen to their stories like a recording device.

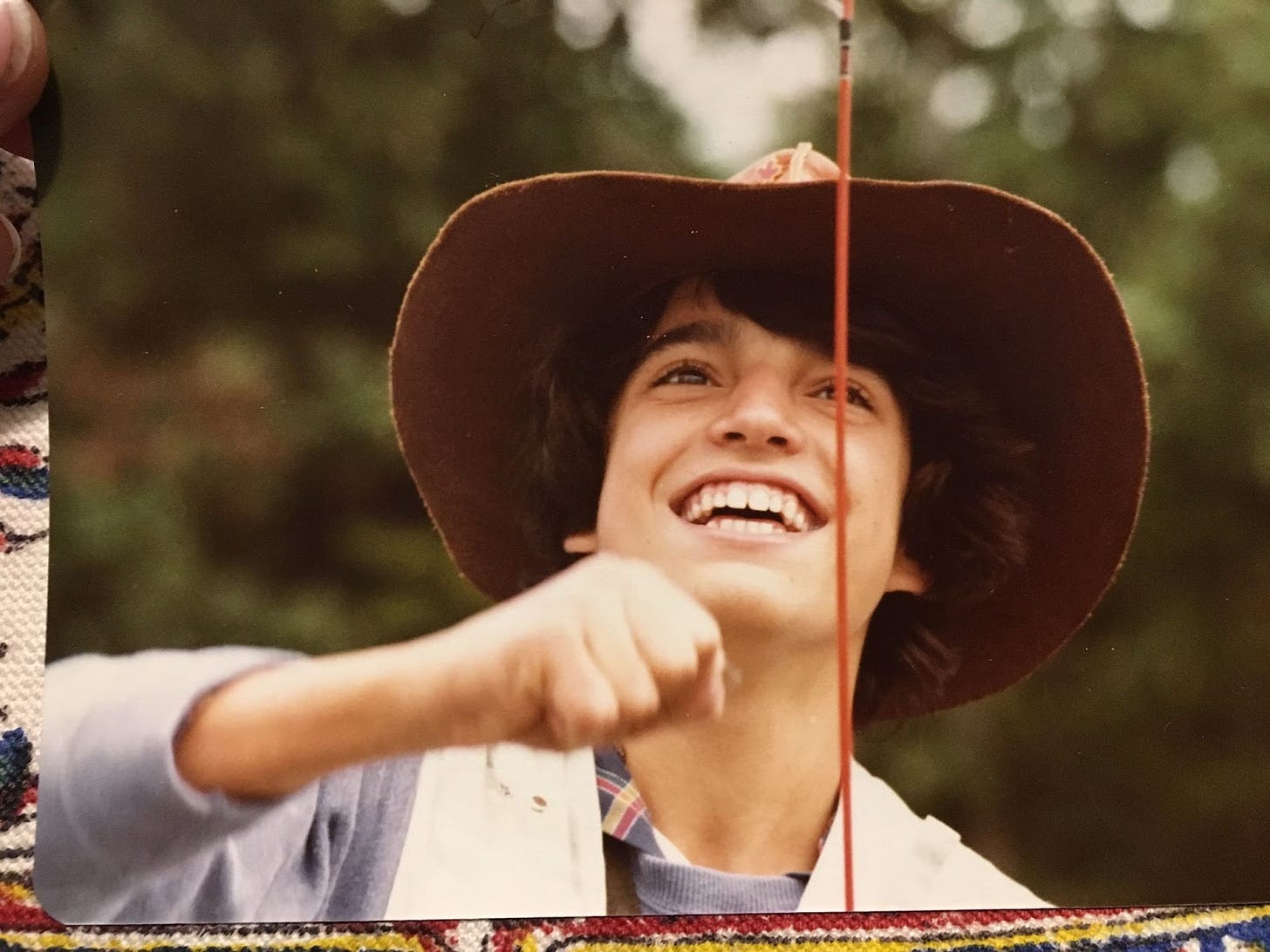

Thankfully some memories were exposed to light, their replication on film taking a load off my brain. It was during my first visit to Chile that my grandmother sat me down to flip through photo albums cataloging her family life in Viña del Mar and my father's early life in Santiago. One photo immediately stood out: a portrait of my dad as a kid, wearing a wide-brimmed suede hat and beaming with unbridled joy at a fishing rod he was working with. The first time I saw it, I couldn’t help but beam too. More clues. I realized then that my father’s love for the water must have been fated; my grandmother’s maiden name, after all, was Marin. People of the sea, joined in matrimony centuries and continents from where they started.

In this family, though, starts and ends are ambiguous. When Jeronimo’s son Bartolome left Spain, he implicated himself and all of his descendants in a colonial regime of expansion, dispossession, and genocide. Ancestors skipped World Wars and built cabins on stolen clearings, only for my grandparents to leave Chile fearing for their lives, driven by dictatorship to become settlers in further unceded lands. These are uneasy trajectories, stalked by blood-tinged footsteps. My parents, living in an easier time and place, decided to travel westwards from Montréal, away from their families but towards better job opportunities and warmer weather. The land now commonly known as Vancouver was meant to be our family’s last stop, but in 2014 I took off with the privilege and naivety of wanting an adventure, one that has not ceased to end for nearly a decade now, and keeps me in a form of permanent limbo, always between people and places. Perhaps due to our shared experiences of movement, I feel increasingly absorbed by my family’s history, thirsty to learn more even if some of the truths may make me never want to drink again.

***

A few of the Chilean photo albums have since come back with my grandmother to Canada and we flip through them together from time to time. I try to keep up with the faded faces she points out, but aside from a few recognizable characters, it’s hard keep everyone straight. As age takes its toll on many of the people staring at me from behind in their plastic sheaths, I grieve for what might get lost forever. So much wisdom, so much history, all these generations of family members with their worlds of hopes and sorrows and eccentricities. I’m not sure if getting to know them is a way of trying or avoiding getting to know myself. Regardless, I’m going to try.

In Vera, my oversharing with the museum curator was rewarded with an impromptu appointment at the town archives around the corner. I wanted to know if Jeronimo de Vera had really been born here, if I was really on my ancestor’s trail. Like everyone we met on the trip, the archivist on duty was extremely friendly. He sat us down and explained that he was going to look through folders of the town’s birth records. The records were “digitized” in the sense that the five hundred years of the Church’s ledgers of handwritten scrawls had been scanned to PDF, but still required someone to look through them entry by entry.

1607, 1607, he muttered. He went quiet for a good 15 minutes, brow furrowed, leaving me trying and find something to do with my hands.

Aha! He finally exclaimed.

¿Lo encontraste? I looked at my partner with wide eyes. It seemed too good to be true.

Not Jeronimo, he told me. But I did find someone named Juan de Vera, born in March of that year.

Juan Vera — the name of the paternal grandfather who forwarded me our family tree in the first place. Could this far more ancient Juan have been our Jeronimo?

The archivist seemed to think that he almost certainly was, but I still don’t know. When I tried to ask in my fumbling Spanish if Juan could have become a Jeronimo, and how my great-uncle could have found him then as Jeronimo in the first place, the archivist merely repeated the name of Juan de Vera’s parents and his birth date, and I was too embarrassed to rephrase the question.

After giving the archivist my email address in case he uncovered anything further, we hopped into the car and went back to the nudist beach, shedding our clothes on the frying pan sand. The gleaming volleyball players were back, and the beach bar with the tragic Caesar salad was a choir of lunch-drunk voices, its patrons merrily sitting bare-bummed on towels draped over plastic chairs. Looming in the distance was a magenta and navy oil tanker, the exact kind I grew up seeing anchored all around Stanley Park — my favourite place in Vancouver, and maybe in the world. All the day was missing was a meticulously rigged fishing rod, and someone to tell me about the precise ebbs and flows of the tide.

I smiled to myself imagining if Jeronimo — or Juan, for all we know — could see it now, the southern horizon that called his son to a future in the Americas but now being lazily watched by an 18-generation descendent in a bucket hat with her A-cups out. Could he ever have had an inkling that one day a Vera daughter would be back on the town’s scorching main avenue, holding up a pocket-sized screen machine with a small blue dot showing her the direction she should walk to trace his footsteps? If so, he would probably tell her to use it to call her dad.

Isabela Bonnevera is a founding editor of Feminist Food Journal.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank my father, Felipe Vera — software wiz, fisherman extraordinaire, and, as it turns out, talented editor — for his thoughtful feedback on this piece. Love you Dad.