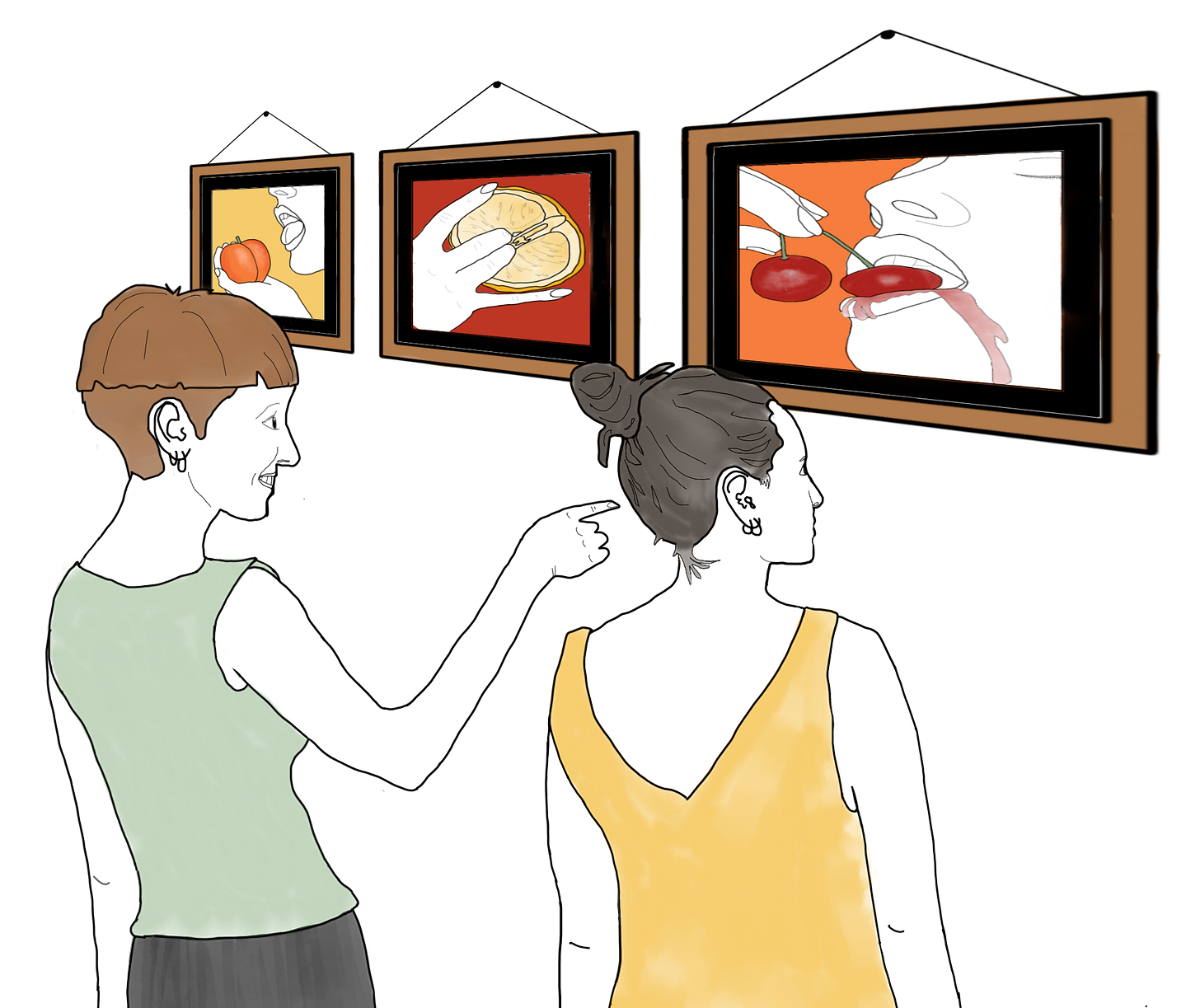

Our third issue, SEX, is here. Equal parts steamy and serious, it explores consumption, performance, empowerment, and subjugation through the lens of food. Read on (or listen to the audio clip above) to find out more about what you can expect from this issue, which we think might just be our juiciest and richest yet.

It was a long, sweaty summer in the Northern Hemisphere, but we aren’t here to cool you off. We’ve been busy watching Erika Lust’s chocolatier and hotpot porn, putting clips of the Milkshake music video in our reels, and critically evaluating the vulvic aura of watercolour oysters. After months of brainstorming, writing, editing, podcasting, and illustrating to a soundtrack of Pony, our SEX issue is hot off the press and ready to land with a sizzle in your inbox.

There’s a lot to take in, with seven written and audio pieces, including, for the first time, a photo essay (in French, no less) and a work of autofiction. So where to start? Whet your appetite with a visual feast of dinner parties in Paris. Go all the way with our longer-form stories grounded in locales as diverse as widow’s ashrams in eastern India, coffee houses in Ethiopia, the gay scene of Chicago, a pig farm in rural Denmark, a college dorm room in Canada, and the New York of late 90s TV.

We’re talking a horny game, but this issue offers serious, and often disquieting, explorations of the interplay between food, gender, sex, and power. We ask: what does it mean to serve, or be served? How do we perform, or un-perform, gender through food and sex? What does it mean to be someone who consumes? How is food used to censor certain kinds of bodies, and certain kinds of sex? What does it mean for our food system to rely on unsettling the boundaries between species and sexualities?

These are big questions, and like all big questions, there are no straightforward answers. Therefore — perhaps most fundamentally — this issue also dives deep into the complexities of the human heart, digging into the desires, fears, questions, and idiosyncrasies that we keep close to ourselves.

The pieces in this issue include:

An Oyster’s Burden | Megan Jones

Be the Boar | Katy Overstreet

Breaking Coconuts | Shirin Mehrotra

Food and Flesh | Isabela Vera

Just Because I Bottom, Doesn’t Mean I’ll Make You a Sandwich | Jay Gee

Meanwhile in Paris | Thomas Jaspers

The Sexualization of Servitude (audio) | Zoë Johnson & Isabela Vera

This time, we’ve taken a stab at reproducing several written pieces as audio readings: An Oyster’s Burden, Be the Boar, and Just Because I Bottom, Doesn’t Mean I’ll Make You a Sandwich all have podcast versions, so please indulge in whatever format your eyes and ears prefer. The last one is available to all listeners, and the first two are for paid subscribers only. Paid subscribers can also listen to Shirin reflect on Breaking Coconuts.

As always, we were impressed by the thoughtful and compelling work brought to us by our authors. One thing that amazes us every time we put together an issue is the resonances that emerge across pieces with seemingly disparate themes. In Jay Gee’s personal essay they explore the connections between their preferences in the bedroom and their performance of feminized labour in the kitchen. They reflect on how this labour makes them subject to gendered perceptions, brewing feelings of discontent and disempowerment vis a vis their cisgender male partner. Similarly, in her interview with Isabela, Zoë discusses the ways that young women’s performance of feminized forms of work in Ethiopia’s coffee houses serves to perpetuate their objectification and their vulnerability to sexual advances from their mainly male clientele. Again, the sexualization of servitude in this context is often disempowering, which Zoë argues, calls into question simplistic narratives around entrepreneurship and empowerment.

Megan Jones and Shirin Mehrotra both write about the ways that food is used as a tool of sexual oppression, but from very different angles. Megan looks at how the film and TV industry reinforce misogyny by failing to show anything other than male genitalia engaging in “mainstream” male-centric sex on screen. Meanwhile, instead of depicting real female and queer body parts, desires, and experiences of pleasure, directors and scriptwriters often use food as a stand-in. Shirin’s article explores how in India, food is weaponized to control women’s sexuality, in turn limiting their reproductive choices and maintaining caste hierarchies. Here, dietary restrictions form the parameters within which one can be considered a good, respectable Hindu woman.

The politics of consumption and consent are addressed, again in unique ways, by both Isabela’s work of autofiction and Katy’s anthropological piece. Food features prominently in the vignettes on sexual exploration, trauma, and discovery in Isabela’s story. Set against the backdrop of a culture that prioritizes pleasure and sexual liberation, Isabela explores the way you can lose yourself — in good ways and in bad — in the rush to consume all of the experiences that life has to offer. Katy’s piece illuminates the ways in which our drive to consume a very different kind of flesh requires boundaries between species, desire, and consent to be blurred in the name of putting bacon on the table.

When we’re deep in an issue, we also begin to see reflections of its ideas on other pages we turn. For example, we see similar reckonings with the complexities of consumption, consent, and our animal nature reflected in Amia Srinivasan’s excellent essay collection, The Right to Sex. In an essay titled “The Conspiracy Against Men”, she describes the response of Brock Turner’s father to his son’s sentencing for the sexual assault against Chanel Miller. She explains how, in his letter to the judge, Dan A. Turner bemoans the loss of Brock’s virile appetite and his love of steak, which, he says, have been so significantly diminished by the ramifications of his crime that Brock “eats only to exist”. Here we see our society’s tendency to associate voracity with masculine power because of the ways in which men are encouraged to consume — both literally (food) and figuratively (bodies) — as they please.

Srinivasan observes how the language Turner uses to describe his son is reminiscent of how one might talk about a golden retriever, rather than an adult human.

In a sense Dan Turner is talking about an animal, a perfectly bred human specimen of wealthy white American boyhood… endowed with a healthy appetite and glistening coat. And, like an animal, Brock is imagined to exist outside the moral order.

But unlike the pigs in Katy’s piece, whose animal-ness strips them of their rights to sex only with consent, in Brock’s case being animal frees him to strip others of that right. Animalness, then, is a tool that can be used to frame both the sexuality of the oppressor and the oppressed, justifying the former’s behaviour and enforcing the latter’s servitude. We see this in the artificial insemination of sows on farms, but also in our treatment of deviant bodies — those of women and femmes, those who perform sexual acts considered outside the norm — that are similarly marked as animal and therefore considered ripe for subjugation. And we see how food frames it all.

Coming up next we have EARTH, CITY, and SEA. As Feminist Food Journal rounds out its first full year of life, we’re still working on figuring out what is our ideal model, and we’d love to hear what you’ve enjoyed so far and would like to see more of. If you’d like to get in touch, our inboxes are always open at hello@feministfoodjournal.com; all readers are also welcome to leave a comment here on Substack. Finally, if you’re not yet supporting us, please consider doing so. Paid subscribers keep Feminist Food Journal going, and we couldn’t do it without you!