Happy Family

Chinese migration, restaurants, and home cooking in New York City

A third-generation New Yorker reflects on how gender and race have influenced labour dynamics in the United States through the prism of her family’s Chinese restaurant in The Bronx.

By Alison Wong | Paid subscribers can listen to Alison read this piece on our podcast.

Before I was born, my grandparents owned a Chinese restaurant called Chow Fon, in Pelham Parkway, a neighbourhood in the Northeast section of the Bronx. It had a yellow awning with large green and red letters, which my Yeh-yeh, or grandfather, kept in the hopes of retaining the clientele of the previous owners. Far from the neighbourhoods with more established Chinese populations, like Manhattan's Chinatown and Queen's Flushing, Chow Fon was among the limited Chinese take-out spots in this northern corner of New York City.

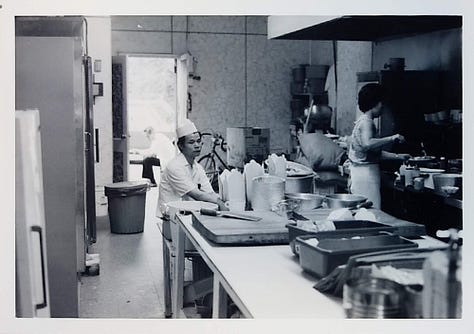

My father remembers Chow Fon feeling like an extension of home. He and my aunt and uncle would work in the restaurant after school, handling the cash register and cycling deliveries. In the kitchen, he recounts, white takeaway food boxes were piled high above the prep counters where wooden chopping boards sat, surrounded by large containers of diced carrots, onions, and celery. The sound of my grandparents swiftly striking pork and chicken with their meat cleavers as they cut it into bite-sized pieces reverberated around the space.

On the stove, pots of flavour-rich sauces simmered — sweet and sour, brown gravy, soy-based marinade — all heavily concentrated with the salty-sweet tastes that characterize Chinese American cuisine. When the chopping was done, my grandparents would stand at their woks, stir-frying dishes over high flames, enduring the heat that blistered from the fryers. They served up barbecued spareribs, fried chicken, and fried rice for a local clientele made up mostly of Jewish and Italian immigrants who populated that area of the Bronx.

By the time I came into the world, the restaurant had been sold. My main experiences of Chinese food were inside the home with my grandparents. More often than not, my Ngin-ngin, or grandmother, could be found in front of the stove, standing tall at 5’4” as she chopped and fried away, engulfed in a cloud of steam from the rice cooker to a soundtrack of sizzling oil from the stove, her lips painted a deep shade of red.

Yeh-yeh, on the other hand, stayed out of the kitchen. A taciturn man, when Yeh-yeh spoke, his deep cadence could almost be felt, like a low rumble. I always thought his tall stature and perfectly coiffed hair gave him the air of a serious businessman. While Ngin-ngin cooked, he often sat with his feet up on a stool in front of him, his arms crossed, his face bathed in the blue light of a Cantonese TV channel.

"Yeh-yeh was the head chef at the restaurant, right? Why does he never cook for us at home?" I once asked my dad, watching as Ngin-ngin tossed onions in the wok.

"He doesn't know how to cook," my Dad replied.

"But didn't he cook at the restaurant?"

"Yes, but that wasn't cooking."

At first, this answer confused me. Hadn’t he spent decades manning the woks, too?

“Take a look behind every kitchen door and you will find a complicated history of cultural migration and world politics," writes Cheuk Kwan in Have You Eaten Yet?: Stories from Chinese Restaurants Around the World. This is certainly true in the case of my grandparents’ restaurant and home kitchen. When my father said that my grandfather "never actually learned how to cook", he really meant that he never learned how to cook homestyle Chinese cuisine.

Instead, as a line cook in Chinese American restaurants, he cooked food tailored to the white American diet. The dishes he prepared bore little resemblance to Ngin-ngin's Cantonese home cooking, which drew on generations of knowledge handed down to her. These dynamics in my grandparents’ household trace the racialized and gendered considerations of immigration and labour in the US — immigration which gave rise to the explosion of Chinese restaurants in the country.

***

My grandfather immigrated to North America from Hong Kong in the late 1950s in search of better economic opportunities, leaving behind my grandmother and my father, who was a young baby at the time. He settled first in Vancouver and entered into work eagerly, saving every penny as he tried to establish a foothold on the new continent before bringing his young family over. He found work in restaurants, as a line cook, taking long shifts behind the stove. After my grandmother and father moved to Vancouver, my aunt and uncle were born. The young couple worked hard to build up their savings before finding a pathway to immigration and moving to New York City.

New York City had already become a hub for the Chinese American community and a locus for the country’s Chinese restaurant scene in particular. The story of Chinese restaurants in the city begins in the mid-1800s when workers — most of whom were young, male, and from rural areas of the Cantonese-speaking Guangdong province in China's south — travelled to San Francisco as labourers during the California gold rush. Many of these men worked for the Central Pacific Railroad, building a rail line from California to Nevada. The conditions of this work were dangerous and exhausting and Chinese labourers received only one-third of the pay of other workers.

By the end of the 1860s, the railway's last spike had been driven into the ground, the gold rush was slowing, the Civil War had ended, and the US economy had begun its slide into the Long Depression of the late 19th century. As jobs dried up, white labourers began to blame the Chinese immigrants, holding anti-Chinese rallies that eventually turned violent; Chinese labourers were forced out of Chinatowns in Western regions and Chinese miners were lynched so the mobs could steal their gold. Meanwhile, the government implemented The Page Act of 1875 — one of the first federal immigration laws — which effectively prohibited the entry of Chinese women into the US, under the assumption that most were sex workers. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese men from entering the US, constructing an entire group as "undesirable" and essentially locking the Chinese community in place, as they no longer had the right to enter and exit the country. Chinese migrants, trapped in the US with dwindling opportunities, began to move eastwards and settle in the enclaves we know now as Chinatowns in states like New York.

Some decades later, these laws would be amended to allow highly-skilled migration, and eventually repealed entirely, but they had a lasting impact on the American economic landscape and the place Chinese immigrants carved out for themselves within it: namely, running restaurants and laundries. This niche, writes Jennifer 8 Lee in her book The Fortune Cookie Chronicles, had everything to do with racial and gender hierarchies: “Cooking and cleaning were both women's work. They were not threatening to white labourers.” These jobs were deemed safe for Chinese men to hold, instead of agriculture, mining, and manufacturing jobs.

In the fifty years between 1870 and 1920, the number of Chinese restaurateurs in New York City exploded from 164 to 11,438, even as the total number of Chinese workers employed in the city went down. The city went from having six Chinese restaurants in 1885 to more than 120 between Fourteenth and Forty-fifth Streets and Third and Eighth Avenues alone just 20 years later.

As Greg Young and Tom Meyers note in an episode of their Bowery Boys podcast, Chinese food became a part of New Yorkers' diet long before bagels, hot dogs, or pizza, making it a cuisine that is "authentically New York". The preferences of New York City's eaters shaped Chinese restaurants' taste, price, and style, as savvy Chinese entrepreneurs worked to increase their cuisines' appeal to American society. Chop Suey was a famous entry point; the city went wild for it. In the early 20th century, this dish fuelled a rising New York City, with bohemians and well-to-dos alike indulging in it during their midday breaks from the office or after nights at the jazz clubs. Eventually, the chop suey craze morphed into a more expansive taste for a cuisine that Lee writes is "more American than Apple pie". Often more heavily fried and sugared, the food offered in America’s Chinese restaurants began to diverge from Cantonese cooking at home. Soy-barbecued spareribs, boneless chicken wings, and beef steak and onions — these dishes were created solely for the American consumer.

***

While my grandmother's home cooking was tied to the preservation of culture, my grandfather's time in the kitchen, cooking Americanized Chinese dishes, was a purely economic pursuit. In other words, my grandmothers' reproductive labour — like that of so many other home cooks — was considered separate from the "productive" work of running a restaurant.

At the same time, although women of my grandmother's generation were traditionally confined to domestic functions such as childcare, cleaning, and cooking, my grandmother tested the boundaries of these traditional gender roles. At Chow Fon, she adopted dual responsibilities as the head of the family's home kitchen and an invaluable restaurant cook. After it was sold, she continued her role as head chef at home. I see her as someone who had agency, both in the home and outside of it.

A table set by Ngin-ngin was a feast for the eyes and the stomach. From Chinese broccoli to Bok choy, the steamed and fried greens would be piled high, slathered in soy and oyster sauces. Bowls of egg noodles with Chinese flower mushrooms and chicken, lightly stir-fried, would waft their juicy aromas. Lobster and black bean sauce would sit at the head of the table, next to traditional Hainanese chicken rice. On festive occasions, such as Chinese New Year, seemingly never-ending dishes would flow out of Ngin-ngin's kitchen, day after day.

Ngin-ngin took pride in being the sole cook in the family and would rarely allow me into her kitchen to help. No matter how much I wanted to be her sous chef, she would instead encourage me to study. Learning math, she said, was more important than cooking. When I would visit my grandparents at home, Yeh-yeh usually only greeted my arrival with a stoic, serious frown. Ngin-ngin, however, would come to greet me with a giant kiss on the cheek — leaving behind a lipstick kiss that I took to be good luck — but she wouldn’t let me follow her back into the kitchen. I wonder how it would have been if I pushed a little more; maybe I could have seen more, caught a glimpse of what she put in her meals.

When my grandparents got older, we began to eat outside of the home — no one in the family was expected to replicate Ngin-ngin's cooking. In Manhattan's Chinatown, we'd dine at restaurants where glass Lazy Susans were set atop white tablecloths. Here, my grandmother's expertise was undeniable. She would frequently comment on the quality of the food: "Too much oil," she would tut. Or, more devastatingly, "That's not how you cook that".

My grandmother was certainly not alone in her discernment. As time has passed, New York City has become home to restaurants serving food in more home-cooked styles; more traditional than the Chinese American fare of restaurants like Chow Fon. One needs only to read about the recent dim sum scandal surrounding Shun Lee's on the Upper West Side to see how seriously New Yorkers take Chinese cuisine. The controversy surrounding the use by copycats of the Shun Lee name is a testament to the quality that customers expect from its head chef, Mr. Wang, who has been credited as the first to bring food that went “beyond Americanized Cantonese cooking” to New York.

If my grandmother had been born in a different generation, I wonder if she would have been in more professional kitchens, donning her apron and serving guests at a larger establishment. I can imagine her cooking different kinds of food, more like those that were served in the home, to her hungry clientele. But it's the Mr. Wangs of this world who are credited with introducing "real" Chinese food to the general public. Despite their immeasurable culinary knowledge and skill, Chinese women still rarely get to use these abilities in professional spaces.

***

Regardless of perceived authenticity, Chinese food and Chinese American food are quintessential parts of New York City. With their knowledge of both traditional and adapted tastes, Ngin-ngin and Yeh-yeh, along with countless other immigrants like them, played a pivotal role in shaping the city into the culinary destination it is today. New York’s Chinese restaurants have become part of the city's fabric, a reflection of the large community of Chinese immigrants who now call the city home. Today, Chinese restaurants feature on many street corners. Everybody has their local favourite.

Whether their role in city-making is recognized, however, is a different matter. Racist labour laws may be a thing of the past, but anti-Asian sentiment in the US remains; we saw this with the increased discrimination and attacks on New York City's Asian community during the pandemic. Restaurants in New York City, and other parts of the nation, faced violent attacks, destruction of property, and countless economic losses. My grandmother passed away in 2011 and my grandfather in 2019, but it’s painful for me to think of what it would’ve been like for my grandparents to live through the pandemic. I’m grateful that they did not have to witness the recent rise of anti-Asian rhetoric and hate crimes, although my father feels that these dynamics have been long brewing in the US. He, like my grandparents, experienced feelings of being stereotyped and othered long before 2020. For their generations, the main goal was to try and survive in America, while resisting the systemic forces of discrimination.

The legacy of that survival can be found in Pelham Parkway. The yellow awning is still on the front of the building where my grandparents' once ran their Chinese restaurant. It’s passed to new ownership now and instead of reading Chow Fon, it displays the name Happy Family. But it continues to serve Chinese takeout to the neighbourhood, playing a small role in New York City’s ecosystem. Most of all, it reminds me of my grandparents’ sweat and sacrifice.

Alison Wong writes about food and her Chinese American heritage. Originally from the Bronx, New York, she received her MA in the Anthropology of Food from SOAS University of London and her BS in Environmental Science from Macaulay Honors College. Find her on Twitter @woalison.

Delicious telling of a history both sweet and sour. I love the way the author reminds us of the racial injustices of the past and present but manages to makes us feel the warmth of her Grandmother’s kitchen and the tenderness of her kiss. Thanks again ffj.

A bittersweet tale, beautifully bookended with the striped awning.