By McKenzie Schwark

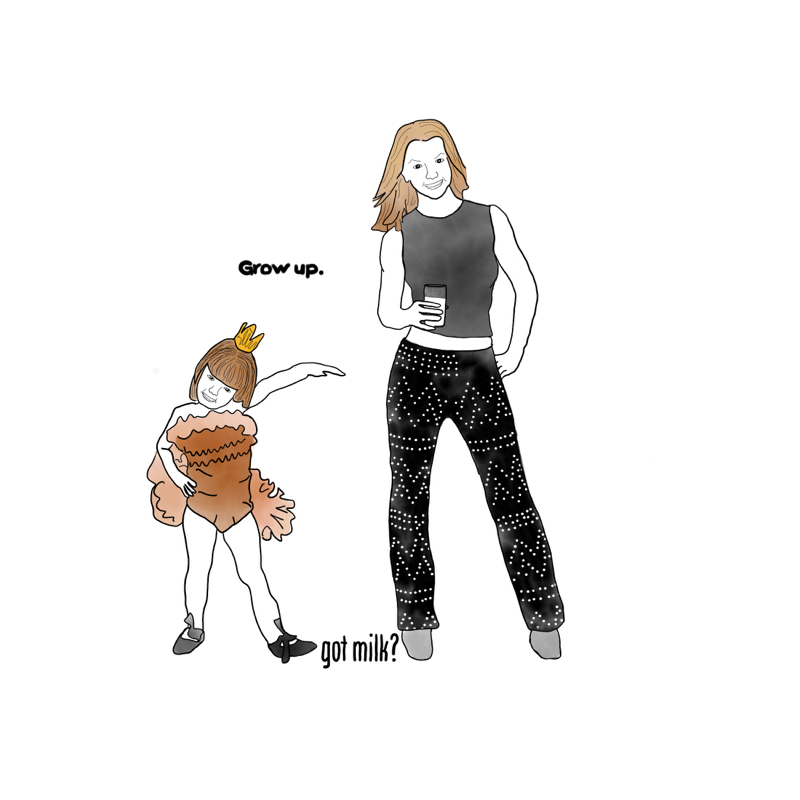

A single piece of decor (if you could call it that) hung in my elementary school’s lunchroom in the heart of the milk-loving American Midwest. For both breakfast and snack time, we were required to choose a baby-sized pink, green, or blue carton from an open fridge just under a giant poster of Britney Spears with a milk mustache, standing over a young dancer. The then-iconic phrase “got milk?” was printed just below her low-rise, studded leather pants.

Milk consumption was at an all-time low when celebrities from Taylor Swift to Kermit the Frog donned the iconic milky stache. On any given day roughly 80% of U.S. consumers were confronted with that simple question: got milk? The historically uncool beverage was suddenly on everyone’s lips.

Around that same time, researchers at the University of North Carolina published a study in the journal Pediatrics that suggested American girls were hitting puberty earlier than was previously considered “normal.” Absent fathers, obesity, and even the popularization of sexual imagery like low-rise jeans were all put forward as possible reasons for this trend.

Scientists and the public were also quick to place milk in the lineup of suspects to blame for the cases of precocious puberty. The anxiety around milk emerged from a distinctly American confluence of unrelenting capitalism, a deep mistrust of the food system, and an obsession with the bodies of women and young girls. What happens with our food and what happens with girls’ bodies tend to be questions we care a lot about but don’t have clear answers for. That opens the door to conspiracy theories that tend to obscure the real problems with American society and our food system.

Precocious puberty

I grew up in a one-glass-of-milk-with-dinner household. I got boobs in the fourth grade. Years later I thought these things might be related. I’d heard somewhere that dairy cows were being pumped full of hormones in order to produce more milk, and those hormones could have seeped into my pre-pubescent adolescent body and changed it.

Precocious puberty is defined as “the appearance of secondary sex characteristics”, such as pubic hair, at an abnormally early age. Until the 1990s, standard medical assumptions about when girls should begin showing signs of sexual maturity were based on a single study that followed 192 white girls’ ascent into puberty in an orphanage in England in the 1960s. It found that girls generally hit puberty sometime after age 11; sexual maturation before age eight only occurred in about one percent of girls in the study.

While working at a pediatric clinic in the 1980s, Marcia E. Herman-Giddens, an associate professor of public health at the University of North Carolina, noticed something peculiar about the girls coming into the clinic. They were showing signs of puberty at a younger age; she was seeing girls with pubic hair and recently developed breasts at ages seven, eight, and nine.

Following these observations, Herman-Giddens led a study of 17,000 American girls between the ages of three and 12 years old. Her team found that “the average age of breast-budding among white girls was 9.9 years while for Black girls it was 8.8.”

“I was very surprised to see how many girls were developing earlier than expected,” said Herman-Giddens. “It was a little shocking and disturbing to see how young a lot of these girls are. It's hard to think that little kids can't just be little kids.”

The differences in findings between white and Black girls could very well have been due to the fact that only 10 percent of participants were African-American. One of the limitations of scientific studies is that there is no way to sample an entire population while taking into account all factors that could skew the end result. Herman-Giddens was no exception. Socio-economic status, food security, mental, emotional, and physical health all play a role in a person’s health and development. Though the sample size was much larger in the American study than the earlier English one, it didn’t prove that girls were hitting puberty earlier so much as it provided a more accurate estimate of the age at which most white American girls hit puberty. But the public’s reaction was much more alarmist.

What makes milk untrustworthy?

For as long as milk has been helping to sustain human life, it has been a seemingly mysterious, and often feared substance.

Drinking dairy milk is a fairly modern endeavour. For most of history, it was primarily used to make food products, but in the 18th and 19th centuries, drinking milk became more popular among Europeans and Americans. That led to a whole bunch of people and babies dying.

Prior to industrialization, drinking milk posed serious health risks, including tuberculosis and scarlet fever. When people began moving away from nursing babies with wet nurses, to giving them cow’s milk, babies began to die at alarming rates: the milk was crawling with bacteria.

In the early 20th century, as pasteurization became common in the US making milk much safer for human consumption, milk’s popularity among the American public grew.

The insatiable American appetite for milk — according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Americans consumed 655 pounds (297 kilograms) of milk products per capita in 2020 — means that dairy is a big business.

For dairy cows to be at their maximum profit potential, they are subjected to an unnatural upbringing that involves being treated with artificial growth hormones. The widespread use of recombinant bovine growth hormone (rbGH) in dairy cows began in 1993, to increase cow milk production. This was thought, by some, to be the reason girls were developing pubic hair and breasts roughly a year earlier than science had defined as the norm.

“Organic milk is a must,” one parent said in an interview with New York Times reporter Lisa Belken, who was reporting on a story on the Herman-Giddens study. “You know, all those hormones in non-organic milk are the reason for early puberty.” None of the mothers could explain how they “‘knew’ this; they just knew,” the article reads.

Milk was, and remains, one of the most highly regulated foods on the American market. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all ingredients and any additional vitamins in milk to be clearly listed among other things like pasteurization, and each state has individual requirements for its production and sale. But even regulation of the food industry is a sore spot for many Americans who don’t trust the government to protect their best interests over corporate power and capital gain. Despite this lengthy list of governmental requirements, or maybe because of it, controversies and conspiracies about milk have never really gone away, they’ve just changed to reflect changes in the world around us.

In the US, we often don’t know much about where our food comes from, which leads to wild conspiracies and mistrust from consumers. One of my aunts told me hot dogs were amputated cow’s lips and I actually believed her because I’ve seen enough Netflix documentaries to entertain just about any food conspiracy. And I’m not alone. Organizations like PETA purport that the US government has been trying to sell off excess milk products since World War I, when it created a demand for milk to send to soldiers overseas. Others believe that the government is stockpiling cheese surplus to keep prices high.

Food manufacturers, food producers, and special interest groups all influence governmental dietary guidelines and food regulation. It leads consumers to wonder: how can you trust an industry to take proper care of you when their bottom line is to make a buck?

When the USDA released updated dietary guidelines in 2015, many experts felt that they had been overly influenced by lobbyists, including Big Dairy’s lobbyists. Big Dairy had ramped up their efforts in the 1990s and 2000s, giving millions to members of Congress, just as those “got milk?” posters hit schools across America. This may have had significant influence over the government’s decision to include milk as such a prominent part of its those dietary guidelines, even though according to Dr. Walter Willett, chair of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health, “there’s just no scientific evidence to support such large amounts of dairy consumption.”

When it comes to nutrition, the hard reality is that the science is constantly changing as we study and learn more, and what we are fed (figuratively) is often what a diet industrial complex and special interest groups want us to eat (literally.) That back and forth reinforces distrust, as does the fact that the diet and nutrition industry is a profitable industry.

In 2001, Dr. Paul Klapowitz, the author of “Early Puberty in Girls,” conducted his own study on precocious puberty’s links to milk. His research concluded that even if the hormones were making their way into the cows’ milk, it would have no effect on America’s girls. The hormones would have to be injected rather than digested to affect the age of puberty.

Despite being debunked, the legacy of the puberty and hormone scare can still be seen today, with the many commercial dairy products that market themselves to consumers as rbGH-free. Why did this theory strike such a nerve in the American psyche?

Obsession and demonization of female bodies in media

Americans are bizarrely obsessed with the bodies and sexuality of girls and women. Our culture’s complicated relationship with sexualization in the media illustrates the tensions between our demand for sex on one hand and our regulation of it on the other, especially if it involves young feminine bodies. A study conducted in 2011 by the University at Buffalo found that 83 percent of women depicted in Rolling Stone magazine were sexualized compared to just 17 percent of men. But anyone who consumes media already knows that.

In 2022, we’re more used to seeing this type of sexualized content, given we have it on-demand in our pockets. You just need to read the comments on a model’s Instagram page to see how obsessed people are with exerting control over the way women use their bodies. But around the time that the milk-hormone theory emerged, the world was changing in big ways: technology’s reach expanded, media became more omnipresent, and girls and young women seemed to be on every magazine cover and MTV video wearing higher cropped tops and lower cut jeans. This so-called sexualization of girls and young women led some in the American public to panic.

It is not too surprising then that milk, a staple food for American children got caught up in this anxiety. It was the perfect scapegoat for those unsettled by the increasingly visible sexualization of young women, even those showing up on the “got milk?” posters. But what was so scary about girls reaching puberty a year or so earlier?

Even Herman-Giddens acknowledged the controversy surrounding her study, which she likened to “The Lolita Syndrome”. It seemed there was a fear that if girls reached sexual maturation earlier, they’d engage in or be subjected to sexual acts earlier. And there is a valid element of that fear, though the proper solution isn’t cutting out dairy. In a country that seems incapable of implementing any kind of useful public sexual health education, vehemently opposed to ensuring universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, and uninterested in addressing the systemic causes of sexual assault and abuse, it makes sense that people would worry about young girls looking more “sexual” at a younger age. Although conspiracy theories, like the milk hormone theory, help to confirm those fears, they don’t do anything to help the very real danger of being a young girl in this world.

Looking back at that “got milk?” poster of Britney and the dancer that hung in my elementary school, I noticed another piece of text. Above the smaller girl’s head, a line of text reads, “Grow up.” The ad is meant to encourage young people to drink milk to accelerate their path to teenager-dom, to look more like Britney Spears. Picturing myself gazing up that poster, as an eight-year-old in the middle of grabbing my daily two-percent carton, is a more sinister scene to me now.

McKenzie Schwark is a writer living in Chicago whose work focuses on reproductive health, chronic illness, and health as a feminist issue. For more, visit mckenzieschwark.com or find her at @schwarkattack.