How I came to realize my body, and especially my gut, is the truest indicator of what I’m feeling, needing, or suppressing through transatlantic moves, never-ending grief, and complex desires.

By Shena Cavallo for our BODY issue | Premium subscribers have access to an audio reading of this piece on our podcast.

When she saw me about to put on my underwear, she waved her hand dismissively and told me not to bother. I might as well go to the bathroom as I was, naked from the waist down. I dropped my underwear, and with them some of my dignity, and initiated my cat-walk of shame toward the bathroom.

I’m generally indifferent to nudity and undress without much thought so it wasn’t her command that bothered me. What irked me was how she acted as if she already knew me. She said it was natural I had loved my dad; fathers benefit from low expectations, whereas mothers always buckle under unrealistic standards. She had gleefully labelled me a “homosexual” as if I was, perhaps, the first real, live one she had ever seen.

The gynecologist was convinced I was hemorrhaging blood, my skin more sallow than usual, because my uterus carried the oppressive weight of generations of trauma — some of my women relatives were indifferent at best to motherhood while others truly suffered because of it, caring endlessly for families regardless of what they wanted

She seemed not to believe that I didn’t want to have a baby: the lemon-sized fibroid in my womb resembled a gestational sac, which she insinuated was an indicator of my latent desires. I felt both defensive and doubtful. I was the same person who had never given my abortion a second thought. I had stood firm in my conviction of not having children, yet, when another gynaecologist had pushed to remove my uterus the week before, I felt resistant.

That’s why I was enduring these small indignities, including her psychoanalysis of my womb. I came with the belief that this gynaecologist might take a more holistic, less invasive approach to the fibroid. But as she ineptly rammed the probe into my vagina with the finesse of a horny adolescent boy, that hope quickly fizzled. Frustrated, she told me to take it and insert it myself. “You’re all up here!” She struck her head with a degree of violence that felt rehearsed. “You’ve got no connection to your body!”

While calling me a “homosexual” and having me parade around half-naked was hardly my idea of foreplay, she probably had a point.

*

My whole life I’ve alternatively felt connected and disconnected from my body. Its expressions, its hunger, its desire, its instincts. This disconnect has often manifested in a rumbling, distraught gut that screams for help after I’ve neglected my body or my emotions for too long. Or simply when I’m not feeling at home in the world.

As a child, I would often feel nauseous in church. I thought it was the incense, but in retrospect I was repulsed by the way that the paper-thin wafer would stick stubbornly to the roof of my mouth, the stinging gulp of wine as hard to swallow as the pedantic lecture about guilt and sin.

At home, eating represented a rare moment of stillness; my family operated with the frenetic pace of working-class people for whom rest is a sunk cost. We rarely partook in “leisure” activities as a family, but we did enjoy our weekly grocery runs. Maybe the food made me feel less alone, as I navigated an out-of-place childhood that turned into a friendless adolescence. As a teenager, after school, I would inhale bowls of sugary cereal and ice cream, almost to the point that I felt sick. My appetite felt insatiable.

My family always enjoyed telling the story of how when a full plate of fish, intended to feed our family of four, was set before me, I ate nearly all of it. Only at the end, as I laboriously chewed the final bites, and bemoaned how large my serving was, they told me that the fish had been intended to feed us all. Unlike Jesus who multiplied the fish, I demolished them.

This is my inheritance, in a way; after all, I am from a family who ate out of tiredness, ate our frustrations in the form of Texas toast, ice cream, Kit Kats. I felt a longing that wouldn't be satisfied with Little Debbie snack cakes. I was hungry to live in a place that was not a Western Pennsylvania, dollar-store, former-factory town, and I was craving connection. Pangs of sexual desire awoke early in me and would manifest in voracious masturbation sessions on my stomach with my face buried in my carpet.

Occasionally men, almost never boys, would spark this. But more significantly, and more out of bounds, I thought of women. I remember daydreaming about a fifth-grade teacher. I squirmed self-consciously in my seat at the movie theatre watching Kate Winslet in Titanic. And I could never look away from the older blonde girl in my dance class with a husky voice and whose hips held potential that I somehow vaguely grasped at 12.

*

Growing up in the US with an Italian father, I had always felt that some part of me didn’t quite fit, maybe that incongruous part was somehow “Italian”. Once I was old enough, I decided to go to Italy and see for myself.

But in Italy, there were no answers to be found. Never was my gut on such high alert as it was when I was living on the outskirts of Rome. There always seemed to be danger lurking, from the men in the dark streets and the subway. I’ve traveled to many countries and find assumptions about which are “safe” and which are “dangerous” , simplistic and often exaggerated or prejudiced, but nowhere did I feel as unsafe as in Rome. It didn’t help that my host brother would creep into my bedroom to stare at me while I pretended to sleep. For weeks, I peed in a plastic bottle rather than going to the bathroom in the middle of the night and risking running into him.

The food in Rome didn’t suit me either. Pasta sank like a rock in my stomach. I was constantly bloated. Nothing in Italy, including Italians, felt familiar. I was reluctantly learning that neither sexual desire nor feeling like a certain geography was “home” were as straightforward as I had hoped.

*

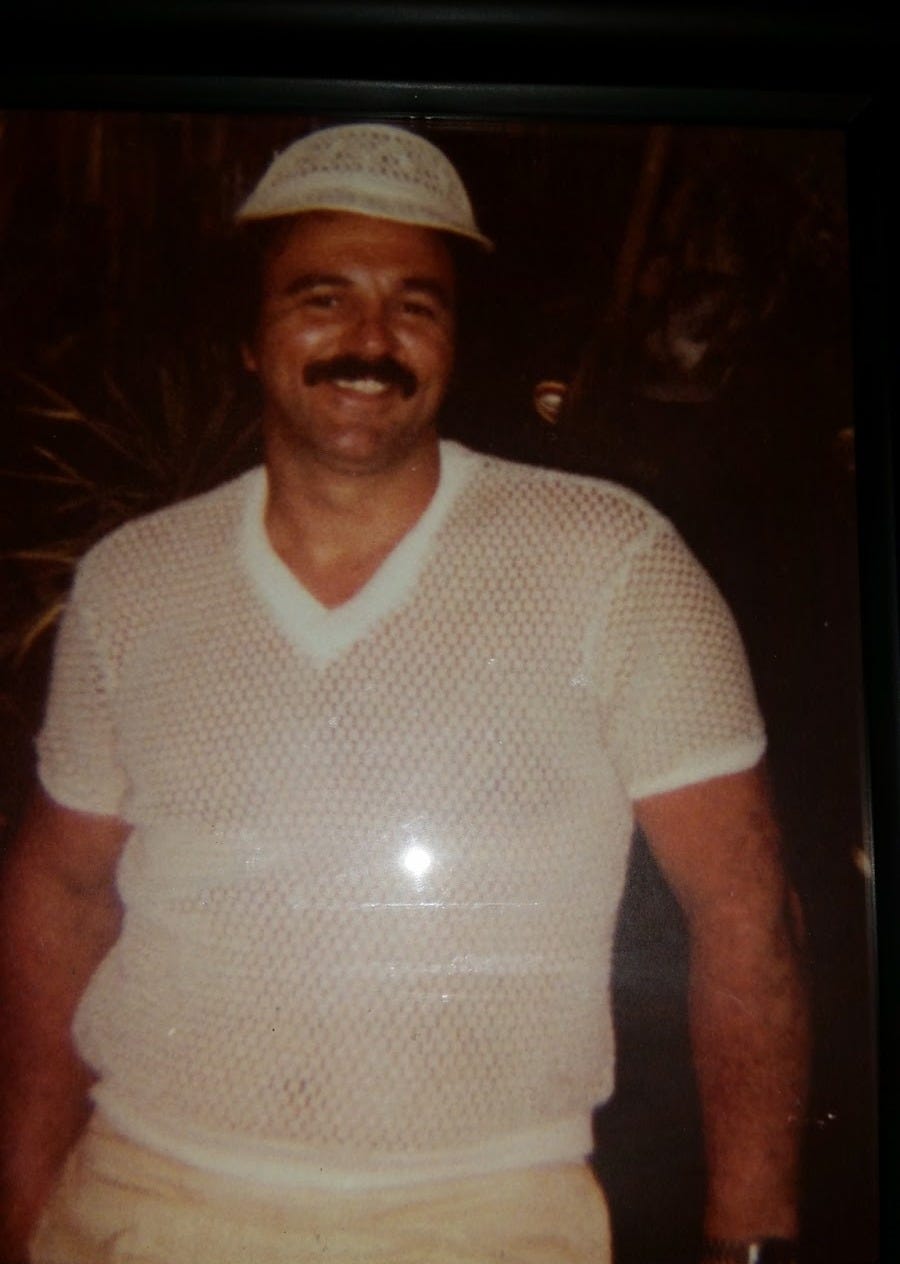

I had thought Italy would feel like home, because for me, home was my father.

My father was a fire sign. A fire of passion, indignation, and resentment burned within him. It burned through his gut and esophagus, ultimately killing him. When my father was dying, my ravenous appetite withered for the first time. Thinking of his yellowing skin and his body taking up less and less space made my throat constrict. I struggled to swallow.

It took us a long time to get doctors to take my dad’s pain seriously. When he complained of pain, one doctor mocked him behind his back, mimicking someone throwing back a bottle while making eye contact with my mother and me. Even if my father had been a drinker, he would’ve still deserved to be treated with dignity and care. But alcohol was not his vice — rather, it was holding and swallowing his emotions, his pain, his shame.

I’ve done the same for many years. Swallowing frustrations, emotions, and desires that scare me or simply those I can’t seem to fully grasp.

I only dated men when I was younger, in part because I met very few queer women. But I also struggled to fully comprehend the rush of excitement and anxiety that marked certain interactions with women — the waves of alternating cold and hot liquid over my body — and where the line between admiration and affection blurred into desire.

It doesn’t escape me that there is something of my dad in the women who draw my attention. Sometimes I think they are like him. At other times I think he would have desired them too. They are always fire signs.

My father and I used to bond over many things. We both loved eating — tomatoes with oregano, oil and vinegar; Italian bread with sugar, melted butter, and cinnamon, pan-fried smelts. We shared a sense of humour and had compatible politics. More importantly, we trusted and understood each other. He once took me out early in the morning to teach me to drive. There was dense, foamy fog and I had never driven on the highway before, but he almost immediately fell asleep, my father who tried to control everything. And I drove with him snoring beside me.

We never extensively talked about the fact that I was queer, not really, though he once alluded to it in our dingy basement as we worked side-by-side, refurbishing some metal and stripping wires that we would go on to sell at the flea market. I was his daughter, but I was also his son, when we both ogled the same actress on TV, when he chastised me for crying with his stern, “man-up” glance, or when he remarked to his friends that I had “balls” as I travelled and moved to new countries. I wonder, though, how my father would see me now; if desiring women would link us in a different way.

*

For years, I used to think my queerness explained my romantic disinterest in men, but I’ve found myself equally indifferent, romantically and physically, to most women I’ve met. Other people seem to fuse into relationships in a way I rarely can.

I suspect neurodivergence explains much of how I navigate my sexuality. Clubs and bars can make me feel overstimulated. I cringe at attempts to flirt. I’m inept at small talk. Certain sensations, sounds, long nails, clingy touching, particular smells — rudely sever any real or imagined interest I had. Much of what electrifies me — banter, the way someone moves — is not apparent over dating apps. Perhaps it’s why if I tend towards anything, it’s one-night stands because if I give someone too much time, the desire evaporates.

It’s not so surprising then that I married the only person I was ever in a relationship with. For a while, I felt anchored by a steadiness, a certainty. I decided to smoke less, drink less and eat more balanced meals. I started to exercise, but I didn’t feel healthier. I vacillated between constipation and diarrhea, my stomach perpetually distended, my joints aching. I couldn’t help but notice that I had felt better in the early days of my relationship, which were marked by midnight espressos, cigarettes, and fast food between marathons of sex.

I see now that it was never about the food, but the malestream of anxiety and chatter in my mind when I’m not fully at home in a situation. In this case, it was the realization that being in a relationship with a man, no matter how much I loved him, would always leave me wondering about something else. No amount of brute force had allowed me to meld my desire into a heterosexual shape. And the six slices of pizza or four donuts, eaten after a day of otherwise “healthy” eating, would not quench what I lacked either.

Initially, I preferred to think my unrest was due to my location, or stalled “career”, so I moved to New York City. There, the buzz of the city only worsened my anxious mind. People competed over who was busier, more important, and consequently more miserable. The food was mostly overpriced and not so different from most of my human interactions there — cold, performative, and devoid of any nutritional value. I was always checking my bank account, trying to stretch a few dollars over several days. And in the background, my relationship was drying up, slowly. Initially, I barely noticed until it was so underwhelming, it rolled under the couch and got lost. Going forward, there would be no one to witness the minutiae of my day and all my future homes would just be marked by me — my books, my habits, my disorder.

*

My father died while I lived in New York. And maybe that’s why I still hate it. It represents the time I’ll never get back. After he was gone, I was adrift. My stomach had never felt emptier and more bloated at the same time. I’d eat slowly, eat blandly, try new diets, see specialists, drink ginger tea and pop antacids, but my stomach would still burn, swell, and churn. Like with my father, the doctors assumed I had a drinking problem. It was just the indigestion of a life half-lived.

And there was always the swell of sadness, starting like a lump in my throat when I would struggle to remember him — his leathery thick red-brown neck tanned from hours of working hunched over under the sun in his beloved garden; his hesitancy to ever hug back, especially once I grew breasts; his powerful back that had helped me learn to swim. His fondness for bland saltines, sardines, and sugary coffee. I can’t even count the number of times I cried on the NYC subway, to blank faces that had long ago stopped registering human emotion.

The grief eventually started to ease up a little, but I didn’t really taste anything anymore. Everyone had insisted if I stopped smoking, my sense of smell and taste would improve. But when I quit, all I noticed was that New York smelt even more of rotting fish, stale menstrual blood, and sewage than I had originally realized.

*

In the years since my dad’s death, I’ve gotten better at trying to find and hold something closer to pleasure, being more in touch with my body. There is no silver lining when someone you love dies. The solitude I feel and felt looms large, repetitive, endless. A gut-wrenching, sinking sensation overwhelms me when I realize I’ll always have to explain something about myself to people, even those I immediately connect with. With my father, I needed no explanation. I was seen and understood in all my stubbornness and my graceless impatience.

But his death did push me to try to live and act on impulse, to listen to my gut. Two years ago, I had the privilege to land and start a new life in Barcelona. Christmas decorations and ‘Bon Nadal” signs were blowing limply in the wind, my suitcase was irretrievably lost, and my only set of clothing had stiffened with dried sweat — hardly an auspicious beginning. To recover, I walked to the beach in a nondescript industrial neighbourhood and watched a couple dance by the sea. The wind was so strong that the music from their small handheld radio was barely audible. My dad was the one who first taught me to swim; we both loved the water.

The waves calmed my lingering unease, and that first week, I ate happily. Very little irritated my sensitive stomach. The optimism and energy I felt in those early days were akin to a feeling I had almost forgotten — falling in love and suddenly feeling that you are capable of believing nonsense.

Unlike New York, which heightened my frenetic tendencies, Barcelona encouraged a slower pace. I quickly settled into a new routine: commuting by bike, leisurely visiting the beach, and chatting endlessly in the evening with friends over just-caught fish, fresh bread, and rainbows of salad.

Two weeks after moving, I met someone and it felt like that day on the beach: an optimistic, safe stillness, like there was no need to rush to the next thing. I had only one goal — I really wanted to make her laugh. And with every interaction, the feeling and the certainty grew, that we had skipped the initial pantomime of desire and flirting and settled comfortably in the small wonders of a life. Unfortunately, the dynamics of our relationship were anything but simple, and in the end, she wasn’t willing to take the risk.

In the aftermath I thought I would sink for a while, then re-emerge unscathed. I’d be able to outrun the disappointment. I’ve always been like that — some people tout it as resilience, but I know it’s really an addiction to dopamine, to distraction. In any case, I had only known her for a few months. But somehow the way she entered a room and tilted her head would have made me feel at home anywhere in the world.

The fall proved endless. I would wake with a terrible sensation like I was drowning or my heart was too big for my chest. But even in the depths of my sadness, I could occasionally glimpse the surface, the horizon past the choppy waves. Maybe it was the conviction, the relief that someone existed capable of jolting me out of the numbness of a life hollowed out in the middle, in the space of my father’s broad shoulders and sturdy, bowed legs.

*

When the tears dried up, I began to bleed. Sitting with a friend in a restaurant, despite wearing so many layers of pads that it felt like a diaper, I soaked through my pants, bled on the chair. The blood dripped down to the carpet and followed me home as I furiously biked up the hill to my house.

The same doctors who had dismissed me, saying I was simply going through perimenopause at 38 and chastising me for not having frozen my eggs while I still had the chance, now realized there was, in fact, a growth in my uterus that was rapidly expanding. The doctors couldn’t believe I was still standing despite so much blood loss. I guess our bodies get used to deteriorated states, in the same way our hearts and guts get used to repressed feelings. It took me almost 40 years, but I realized I needed to listen to my body’s screams. Unfortunately, by then, surgery was the only cure.

Almost nine months after the last time I saw the woman who cracked open my heart, I delivered, so to speak. The doctors removed a lemon-sized fibroid, and my stomach immediately became flatter, less swollen.

I wanted to see the fibroid for myself. I don’t know what I thought I would find in it. Maybe the smell of the dirt of my father’s garden, or the seaweed-infused air from that first day in Barcelona. Would it have felt like the skin on her upper arm or between her nose and lips? In any case, I would have liked to have taken it with me, because I think it could have told me something about the shape of my grief, my sadness, and my longing that continues to elude me. When I woke up, however, they told me they had promptly disposed of it.

*

While the doctors made one last-ditch effort to operate on my father, we stayed in outpatient housing in a small apartment near the hospital. Never a family to go hungry, we brought various snacks. My father couldn’t eat much, but when we laid out our spread, I imagined an alternate reality, one where we were the kind of family that travelled together, who still had many adventures ahead of them. But it was our last “fun” moment. We didn’t laugh together again after that.

The holistic gynaecologist who diagnosed my fibroid as unrealized maternity was wrong; I don’t have any lingering desire to be a parent. But I am always hungry. I am always searching for a home.

In the woman who felt like one, I have to wonder, what did I see? What kind of world did I briefly witness or imagine that led me to unravel and fall so deeply? Maybe it was the missing piece that would complete my clumsy efforts to assemble the set, the props, and the characters to feel like I am home again, sitting with my family over a meal. A happier, queerer version of that family, who I’ve been searching for ever since.

Sometimes, I grasp the feeling briefly. The taste of flavourful tomato, an evening swim in the sea, the jolt of an unexpected connection with another person —the moments may not last, but they are no less significant. I’ll keep looking for them wherever I can.

And now, at least, I rarely crave sugar. I’m learning to better nourish myself.

Shena Cavallo resides in Barcelona with their canine companion, Mr PJ, and occasionally tweets at @ShenaCavallo and documents their travels on Instagram at @shenaletizia. Astrologically, they are driven by earthly pursuits and fiery endeavours, guided by Saturn. This is their first piece, and they hope to further explore grief, home and the ways we experience connections and disconnections with others.

Such a beautiful piece